BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Space exploration

It’s fascinated us for centuries, inspiring astronomers, science fiction writers and more than a few star-gazing entrepreneurs who have plans to launch their own missions to Mars. But will we really ever set foot on the red planet where a year lasts 687 days?

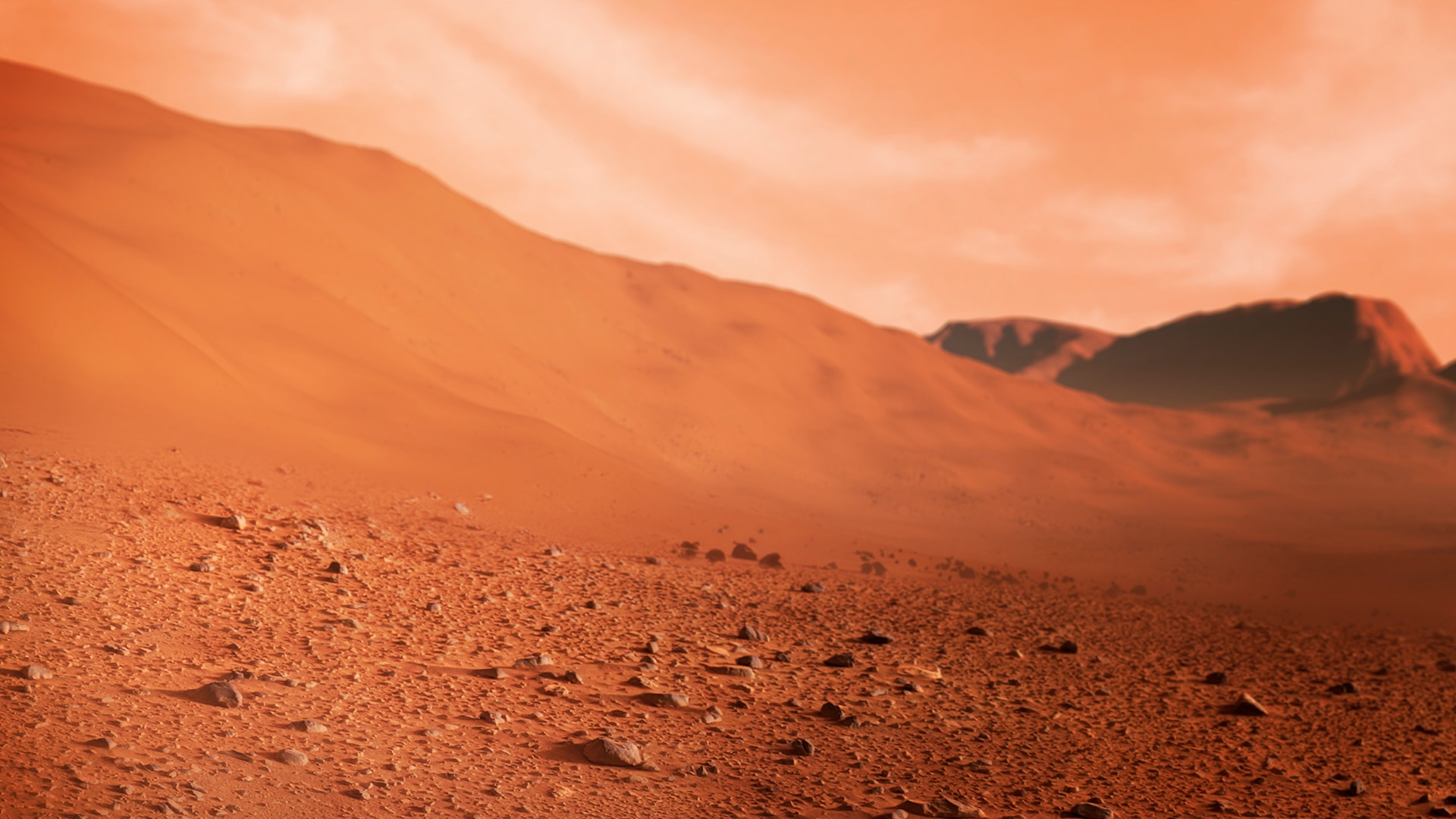

Mars beckons us. The nearest, most Earth-like world to our own, it shines with a reddish glow of reflected sunlight in the night sky, calling out to our curiosity and spirit of adventure. It has an atmosphere (of sorts) and, at noon on a summer’s day, ground temperatures can reach 25˚C. A day lasts about 24 hours, as on Earth... but there the familiarity ends. That atmosphere is 95 per cent unbreathable carbon dioxide, at less than one per cent of the atmospheric pressure on Earth, so there’s little insulation and winter nights can be -140˚C. Mars is a tenth of the mass of Earth, so gravity has only a third of the pull we experience.

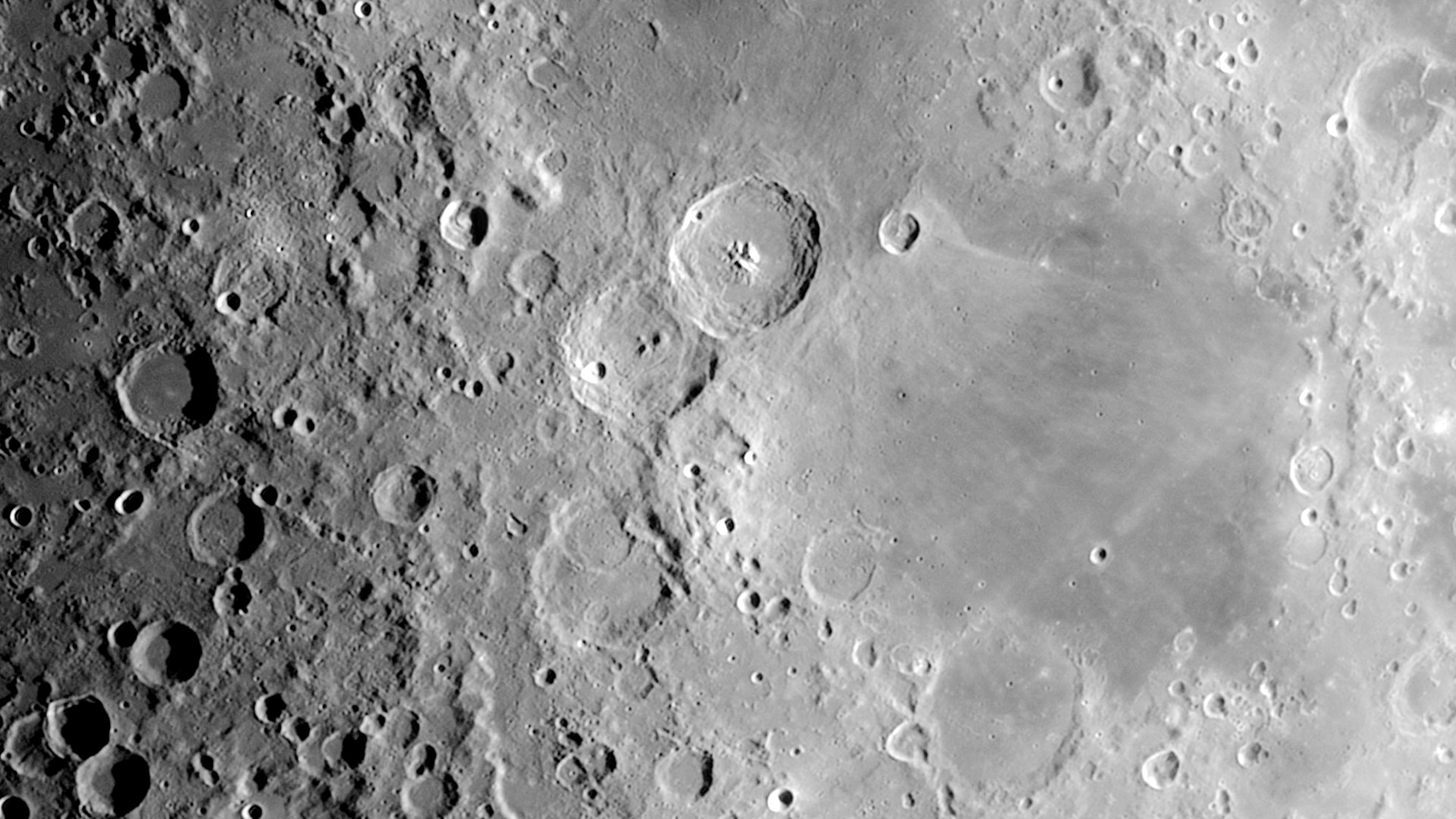

After the Apollo Moon missions in the 1970s, sending astronauts to Mars seemed the next logical step, but it would be a ‘giant leap’, politically and financially. Space is big: while it took the Apollo astronauts only four days to reach the Moon, with present technology it would take about nine months to reach Mars. By the time the planets align favourably for a return, a complete mission might last two or three years. Throughout that time, the astronauts would need food, water and oxygen, plus protection from radiation.

At this point, the success rate for robot missions does not inspire confidence. Russia has launched 21 Mars rockets to date, including five unmanned landers, but only two orbiters completed their missions. The US has been more successful, losing only five out of 23 missions. But there has yet to be a return mission. Clearly some more work is needed before we can contemplate sending humans to Mars. But, sooner or later, we will go. With the political will, it could be within 20 years. And one thing that can be done in the meantime is test human psychological resilience for such a mission. The current record holder for the longest spaceflight is the Russian astronaut Valeri Polyakov, who returned to Earth from Mir in March 1995 after 437 days in space. Such a feat tests the human body’s ability to withstand the muscle and bone loss associated with zero gravity, and is a psychological test of will and endurance. And while contact with astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) is simple, as it takes only a fraction of a second to relay messages to and from Earth, radio signals take 20 minutes to reach Mars, so astronauts there will feel much more isolated, adding to the psychological stress of confinement with a small team.

These testing conditions have been simulated on Earth in order to evaluate their effect on people. Mars 500 was a Russian/European/Chinese project between 2007 and 2011 in an isolation facility in a Moscow car park. It culminated in a 520-day stay by six male volunteers. They claimed to be in good health throughout, but some avoided exercise and hid from their colleagues, and four had difficulty sleeping.

The latest simulation – Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, run for NASA by the University of Hawaii – took place in the Mars-like landscape of Hawaii, 2,500m up the side of the Mauna Loa volcano. A team of six emerged from a year in isolation there on 28 August 2016. They had been allowed out on simulated Mars walks, but only wearing a full space suit; the rest of the time they were living in cramped conditions in a 100sq m geodesic dome. The European Space Agency also performs regular evaluations of the crew at the remote Concordia station in Antarctica to assess the effects of confinement during the long, dark polar winter.

Mars Society president Robert Zubrin has a mission plan that, he believes, will be safer and cheaper than any other. It involves first launching an unmanned Earth Return Vehicle (ERV) that would land on Mars and use solar or nuclear power and imported hydrogen to produce methane and oxygen from Martian CO2. In other words, rocket fuel. This means that humans would set out only once they knew there would be a fuelled return vehicle waiting for them on Mars. The craft Mars Society president Robert Zubrin has a mission plan that, he believes, will be safer and cheaper than any other. It involves first launching an unmanned Earth Return Vehicle (ERV) that would land on Mars and use solar or nuclear power and imported hydrogen to produce methane and oxygen from Martian CO2. In other words, rocket fuel. This means that humans would set out only once they knew there would be a fuelled return vehicle waiting for them on Mars. The craft they fly out on, he says, would stay on Mars to provide future accommodation. A second ERV would be launched at the same time to provide back-up and, if all goes well, would be ready to bring the next team home two years later. In this way, a series of return trips would build up a number of living spaces on Mars for longer stays in the future. And because most of the fuel for the return trip would be made on Mars, Zubrin believes huge energy and cost savings could be made.

NASA’s own plans are more cautious. They involve moving long-duration human missions out from the ISS to orbit the Moon over the next 13 years, while continuing the scientific exploration of Mars; followed up with cargo delivery and an unmanned sample-return mission in the late 2020s. But, they say, it won’t be before the early 2030s that humans orbit Mars, let alone land on the planet. Meanwhile, Elon Musk, former PayPal entrepreneur and founder of SpaceX, has his own plans. He already has a NASA contract for delivering supplies to the ISS and hopes to be able to deliver cargo to Mars in 2018, in preparation for a human mission in the 2020s. ‘Mars is something we can do in our lifetimes,’ he says.

The SpaceX concept has been developed in some detail. Its present Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule are already flying, delivering cargo to the ISS, with both sections returning to Earth for reuse. But the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS) is much more ambitious. Whereas Falcon 9 uses nine Merlin rocket engines, the ITS will use 42 Raptor engines – the same size but with almost three times the thrust. These multiple engines mean that even if some of them failed, a mission could continue. The first test-firing of a Raptor engine went well in September 2016.

The launch rocket would be the most powerful ever built – taller than the Saturn V of the Apollo missions and massively more capable. It could launch 300 tons of cargo into orbit and return to land vertically on the launch pad, ready for reuse with minimal maintenance. As with the Mars Society plan, economies come from fuelling the outward craft in orbit and manufacturing fuel for the return trip on Mars itself. But Musk has his sights set on more than just cargo delivery; he has visions of a Mars colony, and a fleet of hundreds of such craft in the next century. He says he wants to ‘create a self-sustaining civilisation, not an outpost, so humans can become a multi-planetary species’. The orbits of Mars and Earth line up for an effective mission every 26 months, and Musk hopes to use them all from now on, starting with unmanned tests in 2018 and sending the first people to Mars in 2026. Funding might come from governments, private enterprise and even crowdfunding.

Then, far, far in the future, once there are first bases, then colonies, on Mars, comes the challenge of terraforming – making Mars like Earth. That might involve first boosting atmospheric pressure by melting polar carbon dioxide with nuclear power or solar reflectors, and adding to it with imported comets and asteroids. That would also raise temperatures and allow the return of liquid water. But it would need the protection of an artificial magnetic field. Then algae or cyanobacteria could start producing oxygen to make the atmosphere breathable.

The stuff of science fiction, yes, but as we’ve seen, so much of fiction becomes fact.

Featured photograph © Vadim Sadovski