BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Oceans

In a world grappling with the urgent challenges of climate change, a new frontier beckons – the bottom of the sea.

The ocean depths contain the metals needed for the widespread adoption of battery-dependent technologies like electric vehicles, which will help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Interested parties see this as a solution to our technological demands and the pressing need for a “green transition”, but it raises a crucial question: should we mine the deepest stretches of the world’s oceans?

While the ocean is a major carbon sink, absorbing about 25% of all carbon dioxide emissions1 and capturing around 90% of the excess heat2 caused by humans, it also holds vast deposits of rare earth minerals. We’ve known about them since the very first exploration3 of the oceans and their seabed (1872-1876) and now they’re essential for manufacturing batteries and green technologies.

But can we extract these resources safely, without causing irreparable damage to the ocean’s complex ecosystems and everything that depends on them?

Deep-sea mining targets polymetallic nodules – potato-sized rocks found over 4,000 metres below the ocean surface. Rich in minerals such as copper, cobalt, manganese, and nickel, these so-called “batteries in a rock” are the focus of various companies aiming to harvest them.

Advocates of deep-sea mining argue it could be the best – and possibly only – way to meet the growing demand for minerals4 needed in the transition to renewable energy. They also suggest that ocean mining might be less detrimental than current land-based mining practices5 in countries like Indonesia and The Democratic Republic of Congo, where these activities can harm the environment and local communities through deforestation, air pollution, water contamination, and threats to biodiversity.

Conversely, some scientists and activists caution that seabed mining could cause an irreversible chain reaction, severely harming the ocean, depleting biodiversity, and threatening entire ecosystems6 on the ocean floor. There are also potential risks to our health7, including toxic metals entering the human food chain, and the acceleration of climate change. This is all particularly concerning given that these ecosystems are among the least understood on Earth, with a mere 5%8 having been studied and mapped.

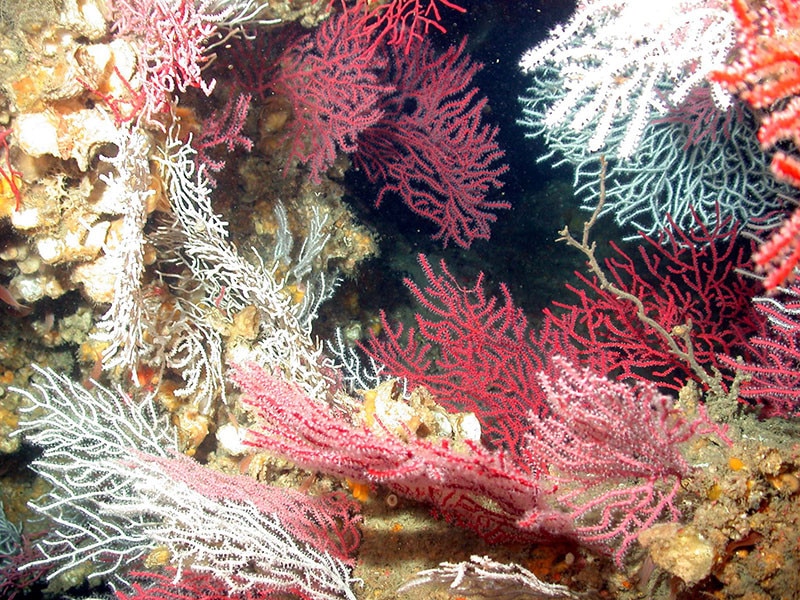

Deep-sea mining uses vacuum technology to suck up nodules from the muddy sediment. However, this process also removes organisms that grow on them, including corals and sponges, many of which cannot grow anywhere else.

In May 2023, scientists discovered more than 5,000 new species9 living in one of the world’s largest mining exploration areas, the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean. The most significant direct impact of mining in these remote ecosystems is the probable loss of habitat and biodiversity.10

The threat of biodiversity loss is one of the reasons more than 780 scientists and marine experts signed a petition11 calling for a pause or ban on deep-sea mining. Among them is Dr Chong Chen, a deep sea biologist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). “There are undoubtedly many undiscovered species with abilities and functions that we cannot even imagine exist,” he says, “and we could lose them without knowing they ever existed.”

Researchers believe that deep-sea species hold the potential to yield valuable compounds, useful in numerous fields including human health. For example, an enzyme crucial for diagnosing the novel coronavirus12 came from a deep-sea microbe living in hydrothermal vents. Furthermore, scientists are intensively studying chemicals from deep-sea sponges, considering them a “drug treasure”13 for potential treatments of a variety of diseases, including HIV14 and cancer15.

The mining process also disturbs seabed sediments and releases them back into the sea, raising additional concerns among scientists.16 “Mining is for metals and some of those may dissolve and be discharged into the water column,” says Jeffrey Drazen, professor of Oceanography with the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “Some of these metals are toxic to life.”

He’s one of the leading scientists in research on the potential impacts of mining operations on mid-water ecosystems, and the possible incorporation of metal compounds into marine food webs. A concern raised by his work is that toxic sediments and dissolved metals could be transported through ocean currents over hundreds of kilometres – far beyond the mining zone – for several years.

Many nations17, including the UK, France, Chile, and Vanuatu – along with the scientific community and international environmental organisations – are also advocating for a pause or complete ban on deep-sea mining. Their objective is to ensure a better understanding of environmental, social, and economic risks – and to explore alternative options – before the world rushes into seabed mining.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a United Nations body overseeing regulations for seabed mining in international waters, aims to complete the regulatory framework by 2025. While the beginning of commercial-scale deep-sea mining in international waters remains uncertain, countries such as Norway are exploring prospects within their own waters, despite growing opposition.18

According to a 2022 report from TDI Sustainability and the World Economic Forum19, the exploitation of mineral resources has been the foundation of modern civilization’s progress. But “civilization as we know it is not sustainable,” notes the report.

“Nothing we do as a human society comes without environmental risks,” reflects Professor Drazen. At the same time, he acknowledges the core challenge is assessing whether the benefits of extracting deep-sea mineral resources outweigh the potential harm to our ecosystem. This ecosystem plays a crucial role in supporting the well-being of our planet and its inhabitants, including serving as a carbon sink and preserving biodiversity – both of which are also essential for combatting climate change. He notes that it’s a tough choice – and we might lack all the necessary information for a definitive answer.

The positive development is that, for the first time, companies, governments, and civil society are actively participating in international discussions to create a regulatory framework for the deep-sea mining industry before it begins.

This issue lies at the centre of a global discussion that probes our relationship with the environment and the effects of new extractive industries. The need for greener technologies and a sustainable future is evident, but the call for research and caution around mining our oceans is resounding.

This article was commissioned as part of 'Our Planet Earth’. This is a digital initiative from BBC Earth, co-produced with Wellcome, bringing you compelling stories of our changing climate and its direct impacts on both wildlife and human health. Discover more here . #OurPlanetEarth.

Header image © Getty

1. Carbon dioxide emissions, 2. Excess heat, 3. First expedition, 4. Demand for minerals, 5. Terrestrial mining 6. Endangering ecosystems 7. Risks to human health, 8. Unexplored oceans, 9. New species discovered in deep-sea mining hotspot, 10. Habitat and biodiversity loss, 11. Pause on deep-sea mining, 12. Deep-sea mining and the coronavirus, 13. Marine sponges as a drug treasure, 14. Sea sponge to HIV medicine, 15. Deep-sea as a source for novel-anticancer drugs, 16. Environmental risk to midwater ecosystems, 17. Government against deep-see mining, 18. Norway mining plans, 19. Decision-making on deep-sea mineral stewardship