BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Hippos are the second biggest animal on land. These water-loving creatures spend most of their time wallowing in mud, but can run at speeds of 22 miles an hour to chase away any trespassers on their territory.

Hippos are the second biggest animal on land. These water-loving creatures spend most of their time wallowing in mud but can be aggressive and dangerous if they feel their territory is being invaded. They eat 50kg of grass every evening and excrete millions of tonnes of poo into Africa’s rivers every year. Because of this, they serve a vital role in feeding the animals and plants in their ecosystem.

Hippopotamuses are the second largest land mammals after elephants.11 The name hippopotamus comes from the ancient Greek words for “river horse”, as these creatures spend most of their time in water or wallowing in mud to keep cool. Hippos can also be found in lakes and mangroves. Common hippos are native to sub-Saharan Africa, and are most closely related to whales, dolphins and porpoises.12 Unlike these aquatic mammals, they can’t swim and so stand on the riverbed. They can’t breathe underwater, and because of their dense bodies and bones, they can’t float either. However, they have developed a way of sleeping underwater – they close their nostrils to keep water out, hold their breath (which they can do for up to five minutes), and sink to the bottom of the river. Whenever they run out of oxygen, they then periodically swim to the top to take a breath, before sinking back down – all without waking up. Hippos have extremely thick, waterproof skin, and short, stout legs. However, don’t let their rather portly, ungainly appearance fool you – hippos can reach speeds of up to 22mph on land over short distances.13

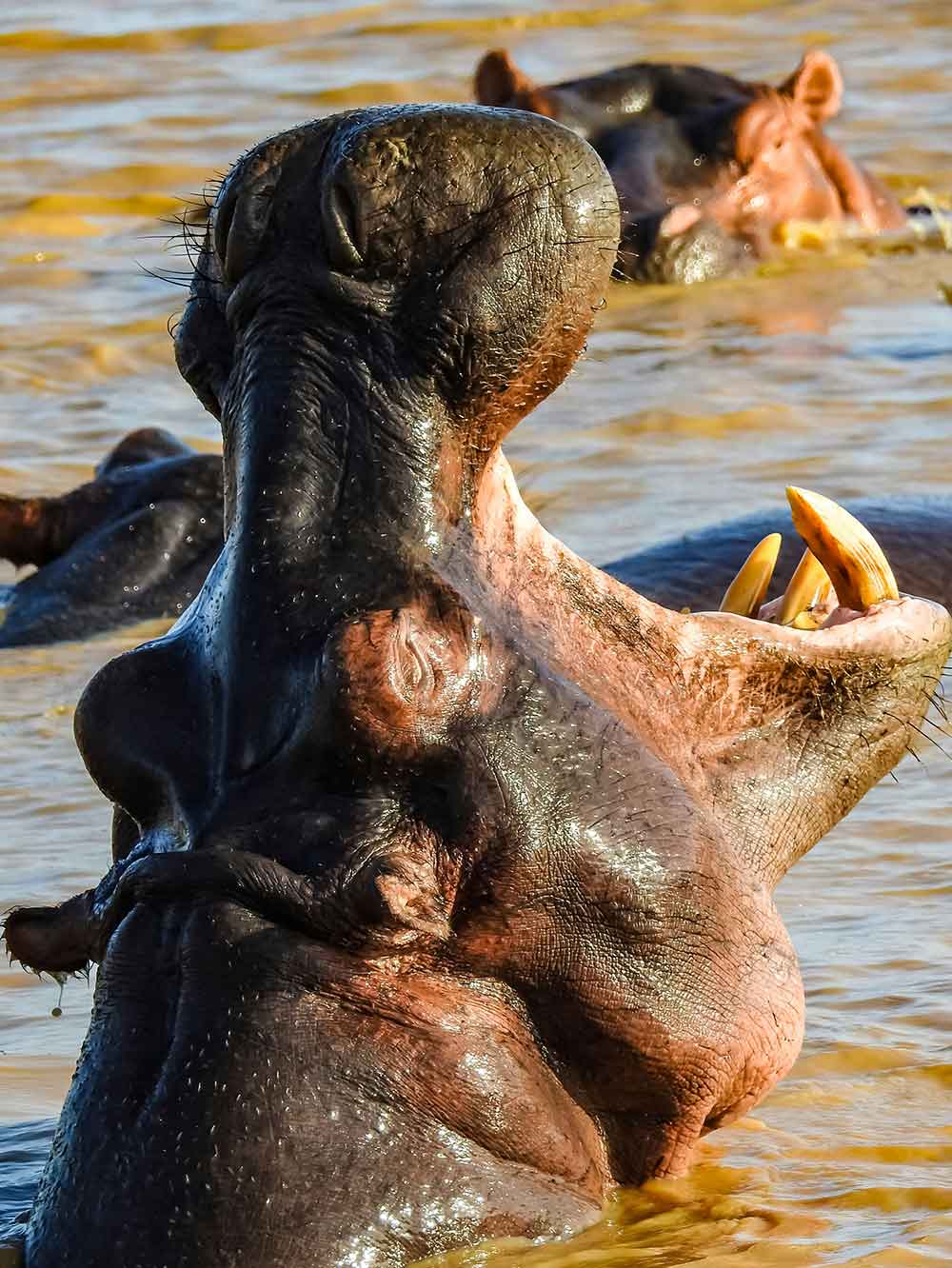

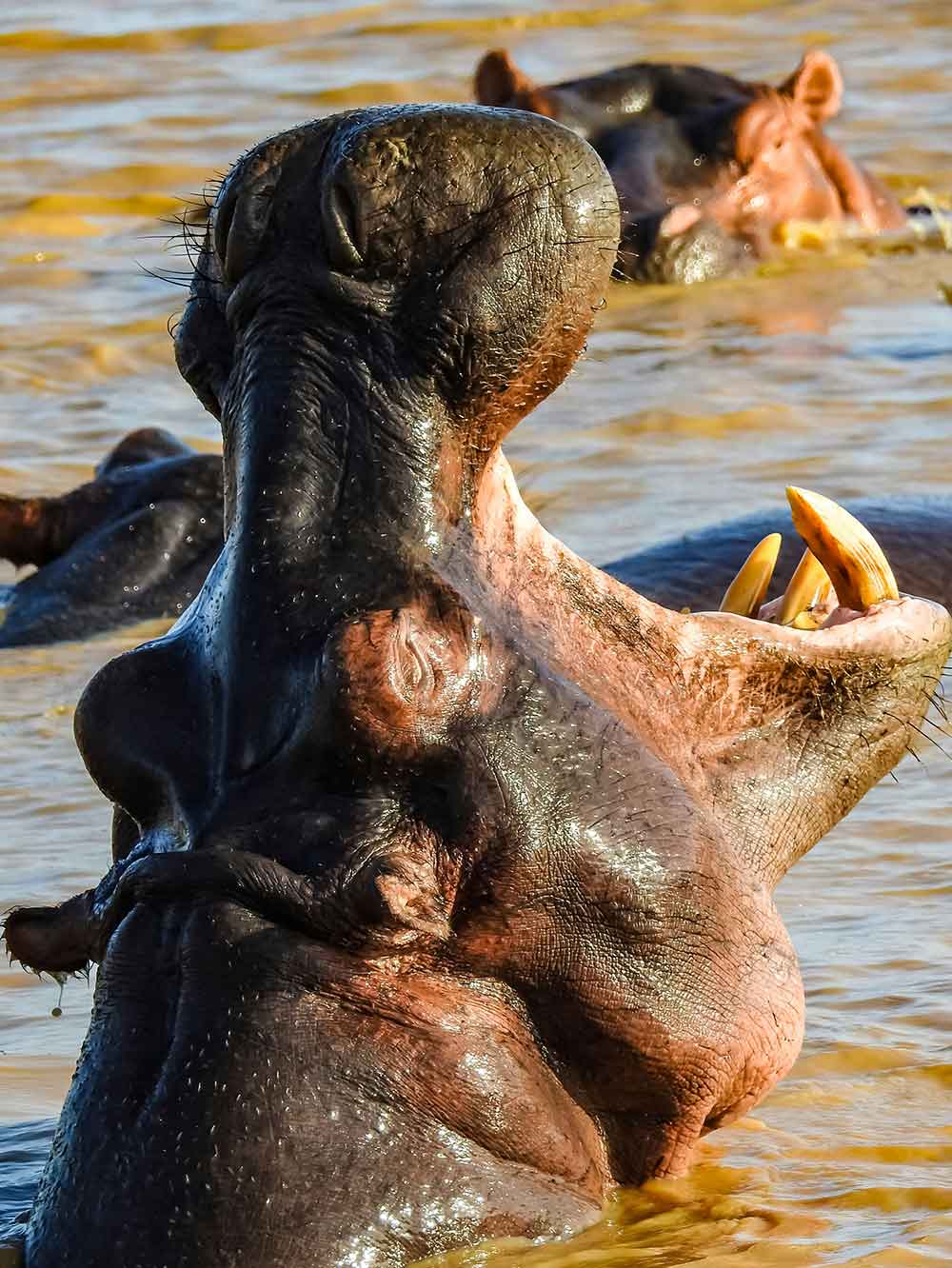

They are also aggressive creatures. Their jaws can open to 180 degrees, and when they bite down, they do so with a strength three times that of a lion.14 They’re also armed with impressive, sharp teeth that can grow up to 50cm long. The preferred plural form of hippopotamus is "hippopotamuses", but "hippopotami" is also acceptable.

Common hippos are native to sub-Saharan Africa. The majority (77%) are located in East Africa, with Zambia and Tanzania boasting the largest hippo populations in the world.15 Other countries with large hippo populations include Mozambique, Uganda, South Africa, Kenya and Zimbabwe. Common hippos spend most of their time in rivers, lakes, and mangroves. Their two-inch-thick skin is tough and waterproof, but it is prone to drying out in the hot African sun. Hippopotamuses protect their hide and keep cool by wallowing in mud and resting in water. When on shore, they also secrete an oily red sweat-like slime, sometimes mistaken for blood, that moistens their skin, has antiseptic properties, and protects them from the sun.16

Intriguingly, there is a growing population of hippos that live in Colombia in South America. This non-native population, referred to as "cocaine hippos", originated from four captive hippos that escaped from the personal zoo of renowned criminal Pablo Escobar – a Colombian drug trafficker and dangerous drug lord.17

Meanwhile a separate species of hippo, known as pygmy hippos (Choeropsis liberiensis), live in the tropical rainforests and swamps of West Africa, including Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Pygmy hippos are about ten times smaller than common hippos, standing at about 1m tall. They are also 20% lighter than a common hippo, have a more rounded head, and have well-separated toes with sharp nails instead of webbed toes. Pygmy hippos and common hippos are thought to have split from a common ancestor around four million years ago.18

Despite their ferocious, aggressive nature, hippos are herbivores. Generally considered to be strict vegetarians, they leave the water to graze at sunset and eat up to 50kg of grass each night.19 An individual hippo requires an area of grass exceeding five hectares within 2 to 5km of a river to maintain a good body condition.20 Hippos prefer short grasses, which are also favoured by other herbivores like zebras and buffalo. They will also eat fruit if it is available, and can use their lips and jaws to tear aquatic plants out of riverbeds.21

However, there are some studies which suggest that hippos are not strict vegetarians after all. In fact, it appears that it is not particularly uncommon for hippos to consume the flesh of carcasses of other animals, and even other hippos. One study found that such scavenging behaviour leaves hippos particularly at risk of anthrax outbreaks.22

Hippos cannot swim or breathe underwater, and their huge bodies are so dense that they cannot float. Instead, they stand, walk, or even run along the bottom of the riverbed. As their eyes and nostrils are on the top of their heads, they can still see and breathe while their bodies are submerged. When their entire body is underwater, hippos close their ears and nostrils to keep water out, and hold their breath, which they can do for up to five minutes.23 Hippos can even sleep underwater, as they have a reflex which causes them to push themselves up to the surface when they need to breathe.

Hippos can reach speeds of up to 22mph on land over short distances, so most humans would have no hope of outrunning them. In fact, one study shows that when running at full pelt, hippos become airborne, lifting all four feet off the ground at once.24 Researchers at the Royal Veterinary College in North Mymms, Hertfordshire, filmed a herd of hippos living at Flamingo Land resort in North Yorkshire. They then pored over the footage. They found that unlike other large land mammals, hippos usually stick to a trotting movement, whatever speed they are moving at. However, if the occasion demands it, for example if they need to chase off a rival hippo, then they can lift off. The analysis showed that when running at top speeds, hippos have all four feet off the ground at once up to 15% of the time.

Hippos are extremely dangerous animals, both from the perspective of other hippos, and from any nearby humans. Their long, sharp canine teeth can reach 20 inches in length, and their jaws can open to an impressive width of 180 degrees. Their bite is reportedly nearly three times stronger than a lion's, and one bite from a hippo could cut a human body in half.25

Although they are vegetarian, hippos can be incredibly confrontational and ferocious creatures. These social animals live together in groups of between 40 to 200 individuals. However, they are highly territorial, and can become violent if something, or someone, trespasses onto their territory. They can run at speeds of up to 22mph, so there is also no chance of outrunning them. According to one estimate, the likelihood of a human dying upon entering a confrontation with a hippo is around 87%, which is higher than that with lions (75%) and sharks (25%).26 While the number of annual human deaths from hippos is unknown, estimates range from about 500 to about 3,000.27

When a hippo dies, and its carcass is left in the sun, methane-producing bacteria generate a build-up of natural gases inside the animal’s stomach. This is part of the natural decomposition process; however, the increasing internal pressure from the gas pushing against the stomach walls can have unexpected consequences. Occasionally, the pressure becomes so great that the body suddenly ruptures, causing an explosion of intestines that can startle nearby animals.28 The process is also known to occur in whales.

Wild hippos are somewhat noisy creatures. Their characteristic "wheeze honks", grunts, squeals, and trumpeting bellows can be heard from over a kilometre away. In the Luangwa Valley in Zambia, the noise they make can reach up to 115 decibels – the equivalent of a rock concert.29

Until recently, the function of their calls was a mystery, however scientists now believe that the distinctive honks allow hippos to tell their friends apart from their foes and recognise individuals from their unique voices.30 To find out more about hippo communication, French researchers led by Prof Nicolas Mathevon from the University of Saint-Etienne, recorded the sounds of hippos living in the Maputo Special Reserve in Mozambique.31 They then broadcast the "wheeze honks" (the loudest of the calls) from the shore of lakes to see how other individuals responded. They found that hippos responded differently depending on whether the hippo call originated from a friend, neighbour, or stranger. They reacted more aggressively to hippos whom they didn’t know, replying with quicker, louder and more frequent calls. These were often accompanied by territorial displays of dung spraying. The researchers concluded that hippos can distinguish between friends, neighbours and strangers from their voices, and can probably tell the difference between individuals too.

The main threats facing hippos are illegal poaching, habitat destruction, and conflict with humans.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies hippos as vulnerable to extinction.32 Hippo populations have declined significantly over recent years. For example, the IUCN estimates a 7-20% decline in the past decade and predicts a further 30% decrease in the next 30 years.33 In Uganda's Queen Elizabeth National Park the number of hippos plummeted from 21,000 in the 1950s to 2,326 in 2005.34 Meanwhile the population of hippos in Virunga National Park in Democratic Republic of the Congo fell from around 29,000 in the 1970s to fewer than 900 in 2005, mostly due to poaching.35

The main threats facing hippos are illegal poaching, habitat destruction, and conflict with humans. Hippos are frequently killed for their meat, fat, and ivory teeth, for example.36 One study calculated that, since 1975, over 770,000kg of hippo teeth have been traded internationally, with most being imported to Hong Kong.37

The pygmy hippo, meanwhile, is classed as an endangered species by the IUCN. Fewer than 2,500 of these solitary forest animals are thought to remain in the wild in West Africa, and only around 350 are left in captivity.38 The main threat to pygmy hippos is poaching and deforestation for mining, logging and agriculture.

Hippos are an example of what is known as ecosystem engineers, which means their very presence changes the habitat in which they live.39 When hippos defecate in rivers, their dung, which is rich in phosphorus and nitrogen, washes downstream and provides vital nutrients to other species, such as plants and aquatic animals.40 Millions of tons of hippo dung enters Africa's aquatic ecosystems every year, so there’s a lot of food to go around.41

For example, researchers at the University of California in Santa Barbara used natural chemical tracers to monitor the flow of nutrients from hippo poo to the tissues of fish and insects.42 They compared fish and dragonfly larvae in two river pools that form part of Kenya’s Ewaso Ng’iro River. One pool was frequently used by hippos, while the second upstream pool wasn’t. They found that during dry periods, fish and dragonfly larvae in the hippo-frequented pool had directly absorbed the hippos’ dung as part of their diet. However, when the river was high and fast flowing, the nutrients were washed downstream before the animals could get to them.

Some scientists are concerned that climate change may alter the beneficial impact of hippos on their environment.43 For example, if rivers do not flow sufficiently – which can happen due to droughts caused by climate change or human water-intensive agricultural practices – then hippo waste can build up, resulting in algae growth and hypoxia (low oxygen) in the water.44

Occasionally, this hypoxia can cause the local extinction of fish and animals, which essentially suffocate. For example, one study found that hippo poo caused the repeated occurrence of hypoxia in the Mara River, in East Africa.45 Researchers documented 49 events over three years that caused oxygen decreases, including 13 events resulting in hypoxia, and four that resulted in substantial numbers of fish dying.

Before the widespread use of DNA data, hippos were thought to be closely related to pigs. However now we know that their closest living relatives are actually cetaceans, the group to which whales, dolphins and porpoises belong. It’s thought that hippos and whales split from a common ancestor around 54–55 million years ago.46 This common ancestor was likely a land-dwelling mammal.47 Modern hippos’ direct descendants were the anthracotheres – an extinct group of plant-eating, semi-aquatic mammals with even-toed hooves that roamed Asia 35 million years ago.48 A 2015 study shed further light on the origin of the common hippo.49 Researchers analysed the remains of a 28-million-year-old animal discovered in Kenya named Epirigenys lokonensis. The creature was about the size of a sheep, weighing around 100kg, about a twentieth the size of modern hippos. Dental analysis of E. lokonensis led the team to conclude that both this mammal and the hippo originated from an anthracothere descendent which migrated from Asia to Africa about 35 million years go. As Africa was then an island surrounded by water, the anthracothere likely swam there. This suggests that the ancestors of hippos were among the first large mammals to colonise the African continent.

However, in the past, hippos weren’t limited to Africa. They once colonised much of Europe, and along with lions and elephants even reached what is now Britain. The teeth of extinct hippo species have even been found beneath Trafalgar Square.50 And also in a cave in Somerset.51 TheSomerset remains, which consist of the tooth of an extinct hippo species Hippopotamus antiquus, suggest that the ancestors of modern hippopotamuses lived in Britain as early as 1.07 to 1.5 million years ago, at a time when the climate in Northern Europe was warm and humid.

Featured image © Aji Vinister | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Wade Lambert | Unsplash

Quick facts:

1. Liam Gravvat. 2022. “What Do Hippos Eat? Here’s What to Know about a Hippopotamus’ Diet.” USA TODAY. September 27, 2022. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/2022/09/27/what-do-hippos-eat/10303668002/.

2. ESC. “Should Hippos Be Added to the Endangered Species List? - Endangered Species Coalition.” Endangered Species Coalition, 23 May 2023, www.endangered.org/should-hippos-be-added-to-the-endangered-species-list. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

3. Ifaw. “Hippopotamus Facts, Diet, and Threats to Survival.” IFAW, www.ifaw.org/animals/hippopotamuses.

Fact file:

1. Innovations Report. 2005. Scientists find missing link between whale and its closest relative, the hippo. https://www.innovations-report.com/life-sciences/report-39309/

2. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

3. Hutchinson JR, Pringle EV. 2024. Footfall patterns and stride parameters of Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) on land. PeerJ 12:e17675https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17675

4. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

5. Chris Klimek. 2024. The Wild Story of What Happened to Pablo Escobar’s Hungry, Hungry Hippos. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/wild-story-what-happened-pablo-escobar-hungry-hungry-hippos-180984676/

6. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

7. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

8. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

9. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

10. Neil F. Adams, Ian Candy, Danielle C. Schreve, An Early Pleistocene hippopotamus from Westbury Cave, Somerset, England: support for a previously unrecognized temperate interval in the British Quaternary record, Journal of Quaternary Science (2021). doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3375

11. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

12. Innovations Report. 2005. Scientists find missing link between whale and its closest relative, the hippo. https://www.innovations-report.com/life-sciences/report-39309/

13. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

14. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

15. World Population Review. 2024. Hippo Population by Country 20204. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hippo-population-by-country

16. Saikawa, Y., Hashimoto, K., Nakata, M. et al. 2004. The red sweat of the hippopotamus. Nature 429, 363 https://doi.org/10.1038/429363a

17. Chris Klimek. 2024. The Wild Story of What Happened to Pablo Escobar’s Hungry, Hungry Hippos. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/wild-story-what-happened-pablo-escobar-hungry-hungry-hippos-180984676/

18. Jason Bittel. 2024. How Moo Deng the pygmy hippo is different from common hippos. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/moo-deng-pygmy-hippo-differences

19. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

20. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

21. International Fund for Animal Welfare. Hippopotamuses. https://www.ifaw.org/animals/hippopotamuses

22. Joseph P. Dudley et al.2016. Carnivory in the common hippopotamus : implications for the ecology and epidemiology of anthrax in African landscapes, Mammal Review. 46, 3, 191 – 203. DOI: 10.1111/mam.12056

23. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

24. Hutchinson JR, Pringle EV. 2024. Footfall patterns and stride parameters of Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) on land. PeerJ 12:e17675https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17675

25. Haddara MM, Haberisoni JB, Trelles M, Gohou JP, Christella K, Dominguez L, Ali E. Hippopotamus bite morbidity: a report of 11 cases from Burundi. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020 Aug 10;2020(8):omaa061. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omaa061. PMID: 32793365; PMCID: PMC7416829.

26. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

27. John P. Rafferty. 9 of the World’s Deadliest Mammals. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/list/9-of-the-worlds-deadliest-mammals

28. Getaway. 2021. Hippo corpse explodes on lion. https://www.getaway.co.za/travel-news/hippo-corpse-explodes-on-lion/

29. The Noise Made by Wild Hippos Can Be Deafening. Smithsonian Youtube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9Mfe3H45_E

30. Helen Briggs. 2022. Hippos can recognise their friends' voices. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-60115512

31. Julie Thévenet, Nicolas Grimault, Paulo Fonseca, Nicolas Mathevon. 2022. Voice-mediated interactions in a megaherbivore. Current Biology, 32, 2, R70 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.017

32. Lewison, R. & Pluháček, J. 2017. Hippopotamus amphibius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T10103A18567364. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T10103A18567364.en.

33. Alexandra Andersson et al. 2018. Missing teeth: Discordances in the trade of hippo ivory between Africa and Hong Kong, African Journal of Ecology. 56, 2, 235 – 243. DOI: 10.1111/aje.12441

34. The University of Hong Kong. 2017. Rampant consumption of hippo teeth combined with incomplete trade records imperil threatened hippo populations. https://phys.org/news/2017-10-rampant-consumption-hippo-teeth-combined.html

35. World Wildlife Fund. 2004. Hippopotamus Video. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?60880/Hippopotamus-Video

36. Alexandra Fisher. 2016. Fighting the Underground Trade in Hippo Teeth. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-watch-hippo-teeth-trafficking-uganda

37. Alexandra Andersson et al. 2018. Missing teeth: Discordances in the trade of hippo ivory between Africa and Hong Kong, African Journal of Ecology. 56, 2, 235 – 243. DOI: 10.1111/aje.12441

38. Elissa Poma. 2024. Why are pygmy hippos so small? And 6 other pygmy hippo facts. WWF. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/why-are-pygmy-hippos-so-small-and-6-other-pygmy-hippo-facts; Better Planet Education. Hippopotamus - Threats to the Hippopotamus. https://betterplaneteducation.org.uk/factsheets/hippopotamus-threats-to-the-hippopotamus

39. McCauley DJ, Graham SI, Dawson TE, Power ME, Ogada M, Nyingi WD, Githaiga JM, Nyunja J, Hughey LF, Brashares JS. 2018. Diverse effects of the common hippopotamus on plant communities and soil chemistry. Oecologia.188, 3, 821-835. doi: 10.1007/s00442-018-4243-y.

40. Jonathan B. Shurin, Nelson Aranguren-Riaño, Daniel Duque Negro, David Echeverri Lopez, Natalie T. Jones, Oscar Laverde-R, Alexander Neu, Adriana Pedroza Ramos. 2020. Ecosystem effects of the world’s largest invasive animal. 101, 5, e02991 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2991

41. Julie Cohen. 2015. The Life Force of African Rivers. UC Santa Barbara, The Current. https://news.ucsb.edu/2015/015281/life-force-african-rivers

42. Douglas J. McCauley, Todd E. Dawson, Mary E. Power, Jacques C. Finlay, Mordecai Ogada, Drew B. Gower, Kelly Caylor, Wanja D. Nyingi, John M. Githaiga, Judith Nyunja et al. 2015. Carbon stable isotopes suggest that hippopotamus-vectored nutrients subsidize aquatic consumers in an East African river. Ecosphere. 6, 4, 1-11 https://doi.org/10.1890/ES14-00514.1

43. Julie Cohen. 2018. Hungry, Hungry Hippos. UC Santa Barbara, The Current. https://news.ucsb.edu/2018/018971/hungry-hungry-hippos

44. Keenan Stears et al. 2018. Effects of the hippopotamus on the chemistry and ecology of a changing watershed. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115, 22, E5028-E5037 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1800407115

45. Dutton, C.L., Subalusky, A.L., Hamilton, S.K. et al. 2018. Organic matter loading by hippopotami causes subsidy overload resulting in downstream hypoxia and fish kills. Nat Commun, 9, 1951 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04391-6

46. UC Museum of Palaeontology. Berkely University of California. 2020. The evolution of Whales. https://evolution.berkeley.edu/what-are-evograms/the-evolution-of-whales/

47. American Museum of Natural History. 2021. Whales and Hippos Evolved Water-Ready Skin Independently https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/research-posts/whale-hippo-aquatic-skin

48. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

49. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

50. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

51. Neil F. Adams, Ian Candy, Danielle C. Schreve, An Early Pleistocene hippopotamus from Westbury Cave, Somerset, England: support for a previously unrecognized temperate interval in the British Quaternary record, Journal of Quaternary Science (2021). doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3375

Hippos are the second biggest animal on land. These water-loving creatures spend most of their time wallowing in mud, but can run at speeds of 22 miles an hour to chase away any trespassers on their territory.

Calf

Bloat, pod, herd

Crocodiles, lions and other big cats. Hyenas can prey on young or weakened hippos

Up to 40 years in the wild. The world's oldest hippo in captivity lived to 65 years of age

An average adult hippo is around 3.5m long and 1.5m tall

Common hippos weigh around 2,000kg, while pygmy hippos are much smaller at around 200-250 kg – about the weight of a large pig

Africa and South America

Between 115,000 and 130,000 common hippos are left in the world.2 There are fewer than 2,500 pygmy hippos left in the wild3

The common hippo is vulnerable, the pygmy hippo is endangered

Hippos can open their jaws 180 degrees, and bite down with a strength three times than that of a lion.

Hippos are the second biggest animal on land. These water-loving creatures spend most of their time wallowing in mud but can be aggressive and dangerous if they feel their territory is being invaded. They eat 50kg of grass every evening and excrete millions of tonnes of poo into Africa’s rivers every year. Because of this, they serve a vital role in feeding the animals and plants in their ecosystem.

Hippopotamuses are the second largest land mammals after elephants.11 The name hippopotamus comes from the ancient Greek words for “river horse”, as these creatures spend most of their time in water or wallowing in mud to keep cool. Hippos can also be found in lakes and mangroves. Common hippos are native to sub-Saharan Africa, and are most closely related to whales, dolphins and porpoises.12 Unlike these aquatic mammals, they can’t swim and so stand on the riverbed. They can’t breathe underwater, and because of their dense bodies and bones, they can’t float either. However, they have developed a way of sleeping underwater – they close their nostrils to keep water out, hold their breath (which they can do for up to five minutes), and sink to the bottom of the river. Whenever they run out of oxygen, they then periodically swim to the top to take a breath, before sinking back down – all without waking up. Hippos have extremely thick, waterproof skin, and short, stout legs. However, don’t let their rather portly, ungainly appearance fool you – hippos can reach speeds of up to 22mph on land over short distances.13

They are also aggressive creatures. Their jaws can open to 180 degrees, and when they bite down, they do so with a strength three times that of a lion.14 They’re also armed with impressive, sharp teeth that can grow up to 50cm long. The preferred plural form of hippopotamus is "hippopotamuses", but "hippopotami" is also acceptable.

Common hippos are native to sub-Saharan Africa. The majority (77%) are located in East Africa, with Zambia and Tanzania boasting the largest hippo populations in the world.15 Other countries with large hippo populations include Mozambique, Uganda, South Africa, Kenya and Zimbabwe. Common hippos spend most of their time in rivers, lakes, and mangroves. Their two-inch-thick skin is tough and waterproof, but it is prone to drying out in the hot African sun. Hippopotamuses protect their hide and keep cool by wallowing in mud and resting in water. When on shore, they also secrete an oily red sweat-like slime, sometimes mistaken for blood, that moistens their skin, has antiseptic properties, and protects them from the sun.16

Intriguingly, there is a growing population of hippos that live in Colombia in South America. This non-native population, referred to as "cocaine hippos", originated from four captive hippos that escaped from the personal zoo of renowned criminal Pablo Escobar – a Colombian drug trafficker and dangerous drug lord.17

Meanwhile a separate species of hippo, known as pygmy hippos (Choeropsis liberiensis), live in the tropical rainforests and swamps of West Africa, including Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Pygmy hippos are about ten times smaller than common hippos, standing at about 1m tall. They are also 20% lighter than a common hippo, have a more rounded head, and have well-separated toes with sharp nails instead of webbed toes. Pygmy hippos and common hippos are thought to have split from a common ancestor around four million years ago.18

Despite their ferocious, aggressive nature, hippos are herbivores. Generally considered to be strict vegetarians, they leave the water to graze at sunset and eat up to 50kg of grass each night.19 An individual hippo requires an area of grass exceeding five hectares within 2 to 5km of a river to maintain a good body condition.20 Hippos prefer short grasses, which are also favoured by other herbivores like zebras and buffalo. They will also eat fruit if it is available, and can use their lips and jaws to tear aquatic plants out of riverbeds.21

However, there are some studies which suggest that hippos are not strict vegetarians after all. In fact, it appears that it is not particularly uncommon for hippos to consume the flesh of carcasses of other animals, and even other hippos. One study found that such scavenging behaviour leaves hippos particularly at risk of anthrax outbreaks.22

Hippos cannot swim or breathe underwater, and their huge bodies are so dense that they cannot float. Instead, they stand, walk, or even run along the bottom of the riverbed. As their eyes and nostrils are on the top of their heads, they can still see and breathe while their bodies are submerged. When their entire body is underwater, hippos close their ears and nostrils to keep water out, and hold their breath, which they can do for up to five minutes.23 Hippos can even sleep underwater, as they have a reflex which causes them to push themselves up to the surface when they need to breathe.

Hippos can reach speeds of up to 22mph on land over short distances, so most humans would have no hope of outrunning them. In fact, one study shows that when running at full pelt, hippos become airborne, lifting all four feet off the ground at once.24 Researchers at the Royal Veterinary College in North Mymms, Hertfordshire, filmed a herd of hippos living at Flamingo Land resort in North Yorkshire. They then pored over the footage. They found that unlike other large land mammals, hippos usually stick to a trotting movement, whatever speed they are moving at. However, if the occasion demands it, for example if they need to chase off a rival hippo, then they can lift off. The analysis showed that when running at top speeds, hippos have all four feet off the ground at once up to 15% of the time.

Hippos are extremely dangerous animals, both from the perspective of other hippos, and from any nearby humans. Their long, sharp canine teeth can reach 20 inches in length, and their jaws can open to an impressive width of 180 degrees. Their bite is reportedly nearly three times stronger than a lion's, and one bite from a hippo could cut a human body in half.25

Although they are vegetarian, hippos can be incredibly confrontational and ferocious creatures. These social animals live together in groups of between 40 to 200 individuals. However, they are highly territorial, and can become violent if something, or someone, trespasses onto their territory. They can run at speeds of up to 22mph, so there is also no chance of outrunning them. According to one estimate, the likelihood of a human dying upon entering a confrontation with a hippo is around 87%, which is higher than that with lions (75%) and sharks (25%).26 While the number of annual human deaths from hippos is unknown, estimates range from about 500 to about 3,000.27

When a hippo dies, and its carcass is left in the sun, methane-producing bacteria generate a build-up of natural gases inside the animal’s stomach. This is part of the natural decomposition process; however, the increasing internal pressure from the gas pushing against the stomach walls can have unexpected consequences. Occasionally, the pressure becomes so great that the body suddenly ruptures, causing an explosion of intestines that can startle nearby animals.28 The process is also known to occur in whales.

Wild hippos are somewhat noisy creatures. Their characteristic "wheeze honks", grunts, squeals, and trumpeting bellows can be heard from over a kilometre away. In the Luangwa Valley in Zambia, the noise they make can reach up to 115 decibels – the equivalent of a rock concert.29

Until recently, the function of their calls was a mystery, however scientists now believe that the distinctive honks allow hippos to tell their friends apart from their foes and recognise individuals from their unique voices.30 To find out more about hippo communication, French researchers led by Prof Nicolas Mathevon from the University of Saint-Etienne, recorded the sounds of hippos living in the Maputo Special Reserve in Mozambique.31 They then broadcast the "wheeze honks" (the loudest of the calls) from the shore of lakes to see how other individuals responded. They found that hippos responded differently depending on whether the hippo call originated from a friend, neighbour, or stranger. They reacted more aggressively to hippos whom they didn’t know, replying with quicker, louder and more frequent calls. These were often accompanied by territorial displays of dung spraying. The researchers concluded that hippos can distinguish between friends, neighbours and strangers from their voices, and can probably tell the difference between individuals too.

The main threats facing hippos are illegal poaching, habitat destruction, and conflict with humans.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies hippos as vulnerable to extinction.32 Hippo populations have declined significantly over recent years. For example, the IUCN estimates a 7-20% decline in the past decade and predicts a further 30% decrease in the next 30 years.33 In Uganda's Queen Elizabeth National Park the number of hippos plummeted from 21,000 in the 1950s to 2,326 in 2005.34 Meanwhile the population of hippos in Virunga National Park in Democratic Republic of the Congo fell from around 29,000 in the 1970s to fewer than 900 in 2005, mostly due to poaching.35

The main threats facing hippos are illegal poaching, habitat destruction, and conflict with humans. Hippos are frequently killed for their meat, fat, and ivory teeth, for example.36 One study calculated that, since 1975, over 770,000kg of hippo teeth have been traded internationally, with most being imported to Hong Kong.37

The pygmy hippo, meanwhile, is classed as an endangered species by the IUCN. Fewer than 2,500 of these solitary forest animals are thought to remain in the wild in West Africa, and only around 350 are left in captivity.38 The main threat to pygmy hippos is poaching and deforestation for mining, logging and agriculture.

Hippos are an example of what is known as ecosystem engineers, which means their very presence changes the habitat in which they live.39 When hippos defecate in rivers, their dung, which is rich in phosphorus and nitrogen, washes downstream and provides vital nutrients to other species, such as plants and aquatic animals.40 Millions of tons of hippo dung enters Africa's aquatic ecosystems every year, so there’s a lot of food to go around.41

For example, researchers at the University of California in Santa Barbara used natural chemical tracers to monitor the flow of nutrients from hippo poo to the tissues of fish and insects.42 They compared fish and dragonfly larvae in two river pools that form part of Kenya’s Ewaso Ng’iro River. One pool was frequently used by hippos, while the second upstream pool wasn’t. They found that during dry periods, fish and dragonfly larvae in the hippo-frequented pool had directly absorbed the hippos’ dung as part of their diet. However, when the river was high and fast flowing, the nutrients were washed downstream before the animals could get to them.

Some scientists are concerned that climate change may alter the beneficial impact of hippos on their environment.43 For example, if rivers do not flow sufficiently – which can happen due to droughts caused by climate change or human water-intensive agricultural practices – then hippo waste can build up, resulting in algae growth and hypoxia (low oxygen) in the water.44

Occasionally, this hypoxia can cause the local extinction of fish and animals, which essentially suffocate. For example, one study found that hippo poo caused the repeated occurrence of hypoxia in the Mara River, in East Africa.45 Researchers documented 49 events over three years that caused oxygen decreases, including 13 events resulting in hypoxia, and four that resulted in substantial numbers of fish dying.

Before the widespread use of DNA data, hippos were thought to be closely related to pigs. However now we know that their closest living relatives are actually cetaceans, the group to which whales, dolphins and porpoises belong. It’s thought that hippos and whales split from a common ancestor around 54–55 million years ago.46 This common ancestor was likely a land-dwelling mammal.47 Modern hippos’ direct descendants were the anthracotheres – an extinct group of plant-eating, semi-aquatic mammals with even-toed hooves that roamed Asia 35 million years ago.48 A 2015 study shed further light on the origin of the common hippo.49 Researchers analysed the remains of a 28-million-year-old animal discovered in Kenya named Epirigenys lokonensis. The creature was about the size of a sheep, weighing around 100kg, about a twentieth the size of modern hippos. Dental analysis of E. lokonensis led the team to conclude that both this mammal and the hippo originated from an anthracothere descendent which migrated from Asia to Africa about 35 million years go. As Africa was then an island surrounded by water, the anthracothere likely swam there. This suggests that the ancestors of hippos were among the first large mammals to colonise the African continent.

However, in the past, hippos weren’t limited to Africa. They once colonised much of Europe, and along with lions and elephants even reached what is now Britain. The teeth of extinct hippo species have even been found beneath Trafalgar Square.50 And also in a cave in Somerset.51 TheSomerset remains, which consist of the tooth of an extinct hippo species Hippopotamus antiquus, suggest that the ancestors of modern hippopotamuses lived in Britain as early as 1.07 to 1.5 million years ago, at a time when the climate in Northern Europe was warm and humid.

Featured image © Aji Vinister | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Wade Lambert | Unsplash

Quick facts:

1. Liam Gravvat. 2022. “What Do Hippos Eat? Here’s What to Know about a Hippopotamus’ Diet.” USA TODAY. September 27, 2022. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/2022/09/27/what-do-hippos-eat/10303668002/.

2. ESC. “Should Hippos Be Added to the Endangered Species List? - Endangered Species Coalition.” Endangered Species Coalition, 23 May 2023, www.endangered.org/should-hippos-be-added-to-the-endangered-species-list. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

3. Ifaw. “Hippopotamus Facts, Diet, and Threats to Survival.” IFAW, www.ifaw.org/animals/hippopotamuses.

Fact file:

1. Innovations Report. 2005. Scientists find missing link between whale and its closest relative, the hippo. https://www.innovations-report.com/life-sciences/report-39309/

2. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

3. Hutchinson JR, Pringle EV. 2024. Footfall patterns and stride parameters of Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) on land. PeerJ 12:e17675https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17675

4. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

5. Chris Klimek. 2024. The Wild Story of What Happened to Pablo Escobar’s Hungry, Hungry Hippos. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/wild-story-what-happened-pablo-escobar-hungry-hungry-hippos-180984676/

6. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

7. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

8. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

9. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

10. Neil F. Adams, Ian Candy, Danielle C. Schreve, An Early Pleistocene hippopotamus from Westbury Cave, Somerset, England: support for a previously unrecognized temperate interval in the British Quaternary record, Journal of Quaternary Science (2021). doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3375

11. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

12. Innovations Report. 2005. Scientists find missing link between whale and its closest relative, the hippo. https://www.innovations-report.com/life-sciences/report-39309/

13. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

14. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

15. World Population Review. 2024. Hippo Population by Country 20204. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hippo-population-by-country

16. Saikawa, Y., Hashimoto, K., Nakata, M. et al. 2004. The red sweat of the hippopotamus. Nature 429, 363 https://doi.org/10.1038/429363a

17. Chris Klimek. 2024. The Wild Story of What Happened to Pablo Escobar’s Hungry, Hungry Hippos. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/wild-story-what-happened-pablo-escobar-hungry-hungry-hippos-180984676/

18. Jason Bittel. 2024. How Moo Deng the pygmy hippo is different from common hippos. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/moo-deng-pygmy-hippo-differences

19. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

20. Wilbroad Chansa, Ramadhan Senzota, Harry Chabwela and Vincent Nyirenda. 2011. The influence of grass biomass production on hippopotamus population density distribution along the Luangwa River in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 3, 5, 186-194. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE.9000107

21. International Fund for Animal Welfare. Hippopotamuses. https://www.ifaw.org/animals/hippopotamuses

22. Joseph P. Dudley et al.2016. Carnivory in the common hippopotamus : implications for the ecology and epidemiology of anthrax in African landscapes, Mammal Review. 46, 3, 191 – 203. DOI: 10.1111/mam.12056

23. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

24. Hutchinson JR, Pringle EV. 2024. Footfall patterns and stride parameters of Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) on land. PeerJ 12:e17675https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17675

25. Haddara MM, Haberisoni JB, Trelles M, Gohou JP, Christella K, Dominguez L, Ali E. Hippopotamus bite morbidity: a report of 11 cases from Burundi. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020 Aug 10;2020(8):omaa061. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omaa061. PMID: 32793365; PMCID: PMC7416829.

26. National Geographic. 2011. Hippopotamus. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/hippopotamus

27. John P. Rafferty. 9 of the World’s Deadliest Mammals. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/list/9-of-the-worlds-deadliest-mammals

28. Getaway. 2021. Hippo corpse explodes on lion. https://www.getaway.co.za/travel-news/hippo-corpse-explodes-on-lion/

29. The Noise Made by Wild Hippos Can Be Deafening. Smithsonian Youtube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9Mfe3H45_E

30. Helen Briggs. 2022. Hippos can recognise their friends' voices. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-60115512

31. Julie Thévenet, Nicolas Grimault, Paulo Fonseca, Nicolas Mathevon. 2022. Voice-mediated interactions in a megaherbivore. Current Biology, 32, 2, R70 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.017

32. Lewison, R. & Pluháček, J. 2017. Hippopotamus amphibius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T10103A18567364. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T10103A18567364.en.

33. Alexandra Andersson et al. 2018. Missing teeth: Discordances in the trade of hippo ivory between Africa and Hong Kong, African Journal of Ecology. 56, 2, 235 – 243. DOI: 10.1111/aje.12441

34. The University of Hong Kong. 2017. Rampant consumption of hippo teeth combined with incomplete trade records imperil threatened hippo populations. https://phys.org/news/2017-10-rampant-consumption-hippo-teeth-combined.html

35. World Wildlife Fund. 2004. Hippopotamus Video. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?60880/Hippopotamus-Video

36. Alexandra Fisher. 2016. Fighting the Underground Trade in Hippo Teeth. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-watch-hippo-teeth-trafficking-uganda

37. Alexandra Andersson et al. 2018. Missing teeth: Discordances in the trade of hippo ivory between Africa and Hong Kong, African Journal of Ecology. 56, 2, 235 – 243. DOI: 10.1111/aje.12441

38. Elissa Poma. 2024. Why are pygmy hippos so small? And 6 other pygmy hippo facts. WWF. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/why-are-pygmy-hippos-so-small-and-6-other-pygmy-hippo-facts; Better Planet Education. Hippopotamus - Threats to the Hippopotamus. https://betterplaneteducation.org.uk/factsheets/hippopotamus-threats-to-the-hippopotamus

39. McCauley DJ, Graham SI, Dawson TE, Power ME, Ogada M, Nyingi WD, Githaiga JM, Nyunja J, Hughey LF, Brashares JS. 2018. Diverse effects of the common hippopotamus on plant communities and soil chemistry. Oecologia.188, 3, 821-835. doi: 10.1007/s00442-018-4243-y.

40. Jonathan B. Shurin, Nelson Aranguren-Riaño, Daniel Duque Negro, David Echeverri Lopez, Natalie T. Jones, Oscar Laverde-R, Alexander Neu, Adriana Pedroza Ramos. 2020. Ecosystem effects of the world’s largest invasive animal. 101, 5, e02991 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2991

41. Julie Cohen. 2015. The Life Force of African Rivers. UC Santa Barbara, The Current. https://news.ucsb.edu/2015/015281/life-force-african-rivers

42. Douglas J. McCauley, Todd E. Dawson, Mary E. Power, Jacques C. Finlay, Mordecai Ogada, Drew B. Gower, Kelly Caylor, Wanja D. Nyingi, John M. Githaiga, Judith Nyunja et al. 2015. Carbon stable isotopes suggest that hippopotamus-vectored nutrients subsidize aquatic consumers in an East African river. Ecosphere. 6, 4, 1-11 https://doi.org/10.1890/ES14-00514.1

43. Julie Cohen. 2018. Hungry, Hungry Hippos. UC Santa Barbara, The Current. https://news.ucsb.edu/2018/018971/hungry-hungry-hippos

44. Keenan Stears et al. 2018. Effects of the hippopotamus on the chemistry and ecology of a changing watershed. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115, 22, E5028-E5037 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1800407115

45. Dutton, C.L., Subalusky, A.L., Hamilton, S.K. et al. 2018. Organic matter loading by hippopotami causes subsidy overload resulting in downstream hypoxia and fish kills. Nat Commun, 9, 1951 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04391-6

46. UC Museum of Palaeontology. Berkely University of California. 2020. The evolution of Whales. https://evolution.berkeley.edu/what-are-evograms/the-evolution-of-whales/

47. American Museum of Natural History. 2021. Whales and Hippos Evolved Water-Ready Skin Independently https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/research-posts/whale-hippo-aquatic-skin

48. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

49. Lihoreau, F., Boisserie, JR., Manthi, F. et al. 2015. Hippos stem from the longest sequence of terrestrial cetartiodactyl evolution in Africa. Nat Commun 6, 6264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7264

50. Mike Unwin. Hippo guide: how big they are, what they eat, how fast they run - and why they are one of the most dangerous animals in the world. Discover Wildlife. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-hippos

51. Neil F. Adams, Ian Candy, Danielle C. Schreve, An Early Pleistocene hippopotamus from Westbury Cave, Somerset, England: support for a previously unrecognized temperate interval in the British Quaternary record, Journal of Quaternary Science (2021). doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3375

Calf

Bloat, pod, herd

Crocodiles, lions and other big cats. Hyenas can prey on young or weakened hippos

Up to 40 years in the wild. The world's oldest hippo in captivity lived to 65 years of age

An average adult hippo is around 3.5m long and 1.5m tall

Common hippos weigh around 2,000kg, while pygmy hippos are much smaller at around 200-250 kg – about the weight of a large pig

Africa and South America

Between 115,000 and 130,000 common hippos are left in the world.2 There are fewer than 2,500 pygmy hippos left in the wild3

The common hippo is vulnerable, the pygmy hippo is endangered

Hippos can open their jaws 180 degrees, and bite down with a strength three times than that of a lion.