BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

With thousands of species and countless individuals, catfish are among the most abundant and adaptable freshwater fish on Earth. These remarkable creatures don’t just swim – they can walk on land, climb walls, and even breathe air, making them one of the most surprising fish in nature.

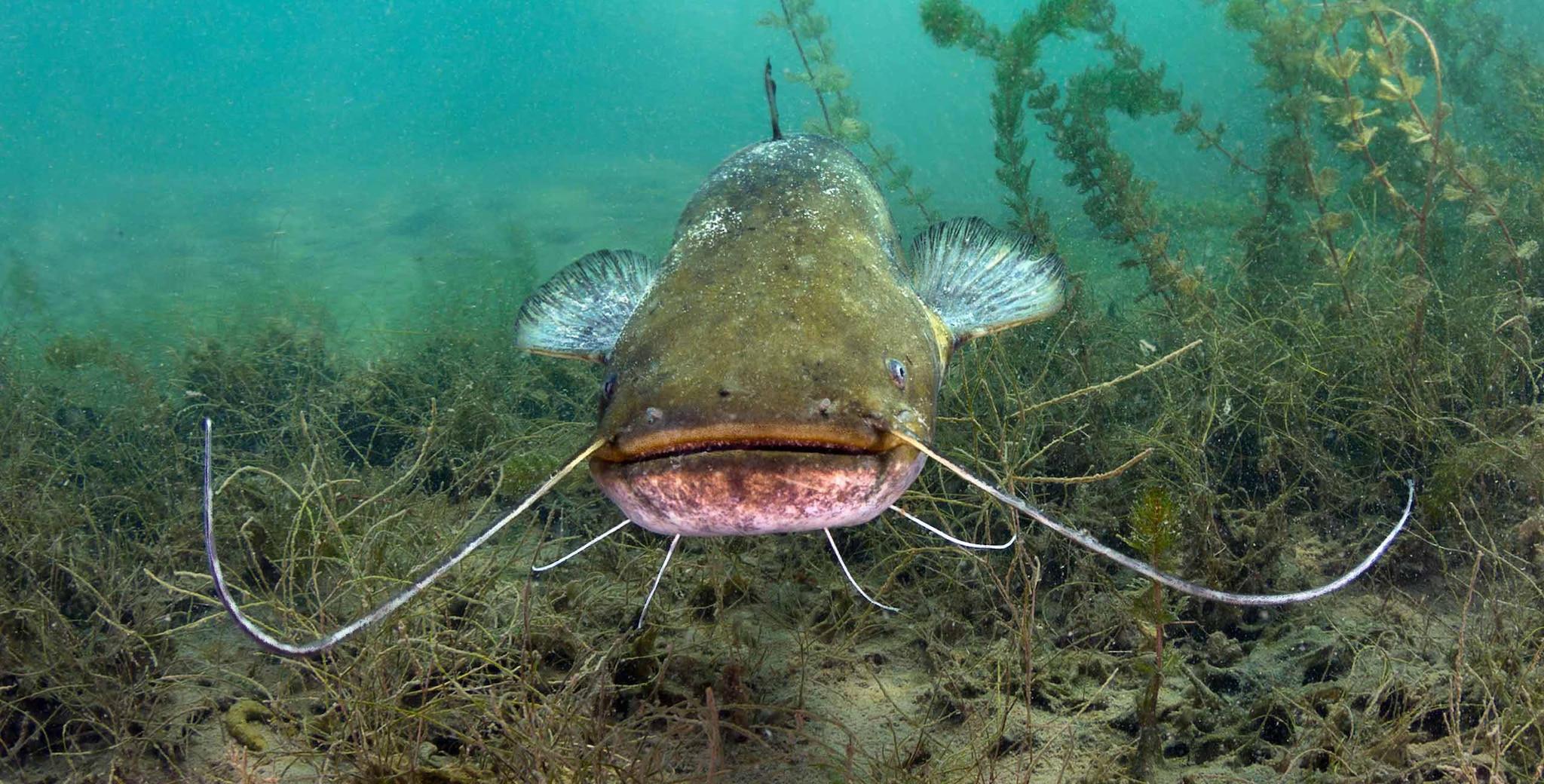

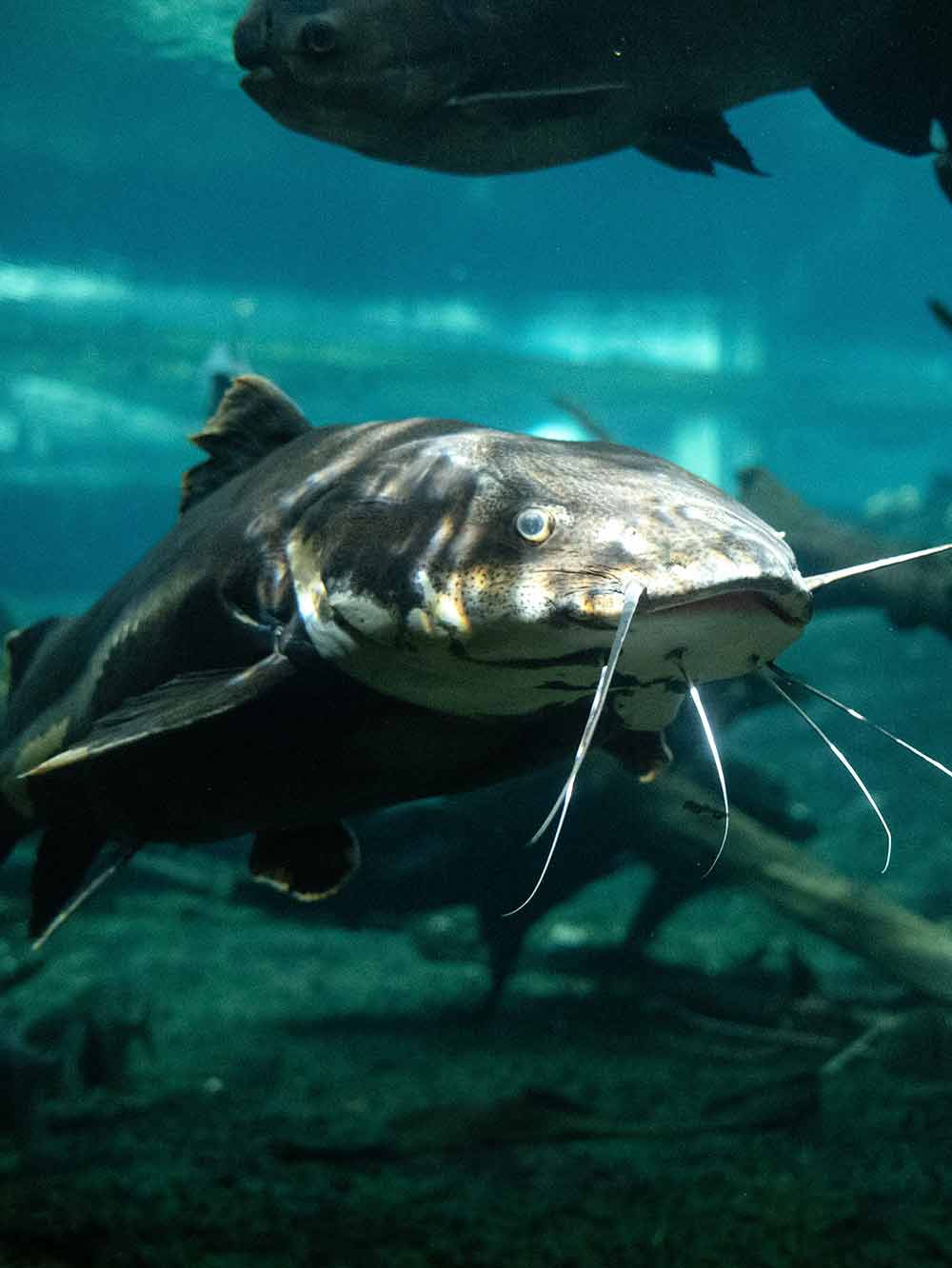

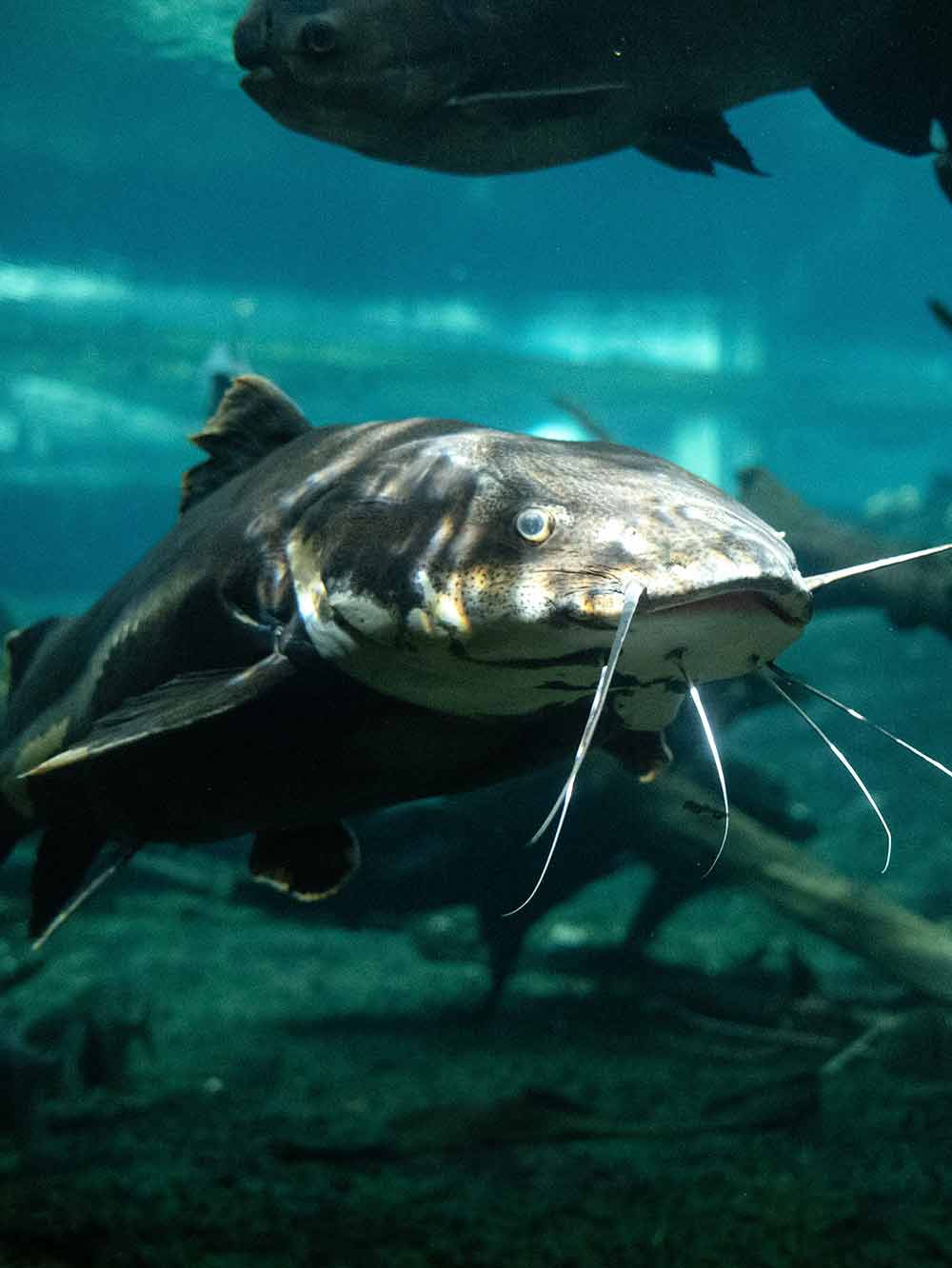

Catfish can be characterised by their wide, fleshy lips, sausage-like bodies and whiskery faces which give them their name. The abundance of some catfish species and unusual looks of others make them a popular target for sport fishers and aquarium enthusiasts.1 Most catfish are bottom dwellers, meaning they sweep along the bottom of rivers, lakes, estuaries and other bodies of freshwater. Catfish belong to one of the largest orders of fish. This diverse group contains both critically endangered species, such as the Mekong giant catfish, primarily found in the Mekong River basin in Southeast Asia, and highly invasive species, such as the walking catfish, which has established itself in Florida.2

There are between 34 and 44 families of catfish and at least 3,400 different species, depending on taxonomic classification.13 Some of the smallest catfish include the pygmy corydoras, which are popular aquarium additions and measure 3cm head to tail; the Pareiorhina hyptiorhachis, native to fast-flowing little streams in South America which measure approximately 3-3.5cm in length; and the shiny, eel-like candiru catfish which can be as small as 1.2cm.14 The Mekong giant catfish and Goonch catfish, both found in the Mekong river, are the heaviest species and can weigh over 100kg, whilst the Wels catfish found in European waters is the longest, reaching a maximum length of 5m. The piraiba in the Amazon can grow to 4m. Large catfish usually migrate huge distances and create ecological links between parts of a river miles apart.15

Suckermouth catfish are also known as algae-eaters for their tendency to latch onto the glass walls of aquariums and fastidiously consume algae.16 Long-whiskered catfish have particularly long barbels trailing from their snout. All catfish are extremely sensitive to their environments, but some have developed truly fascinating abilities: electric catfish can discharge up to 350 volts and are seemingly immune to high shocks themselves.17 Japanese sea catfish can detect the minute changes in water pH that sea worms create by exhaling carbon dioxide to help them locate prey.18

Catfish, like other fish, take in oxygen through their gills. However, there is one family within the Siluriformes order known as "airbreathing catfish" (Clariidae), which, as the name suggests, can swim up to the surface and gulp in air.19 They have evolved this ability to cope with hypoxic (low oxygen) environments. The striped catfish for example, lives in heavily polluted waterways in Southeast Asia, where the oxygen levels in the water are very low.20 To survive, it must surface for air which then diffuses into the blood. In the airbreathing corydoras catfish, there is a phenomenon of group airbreathing, which helps reduce vulnerability to predators.21

The catfish's capacity to adapt does not end there; its airbreathing abilities have allowed some to become fish out of water. The walking catfish, another airbreathing species, sometimes resembles a dark, bloated slug and can survive for 18 hours, moving up to 1.2km on land.22 Much like slugs, the walking catfish is often seen after periods of rain or flooding. Their long and sweeping barbels help them navigate both water and land. In 2021 scientists coined a new term – "reffling" – after studying the movement of the armoured suckermouth catfish which uses its mouth, tail and a "grasping" pelvic fin to haul itself across dry ground.23 They can last up to 30 hours out of water, provided a layer of mucus keeps them moist. Similarly, some catfish have a climbing style known as "inching", where they alternate between using suction from their mouths and their pelvic disc to shuffle up vertical cave walls.24

The catfish’s diet includes fish, molluscs, algae, plants, phytoplankton, fish eggs, and even other catfish. Both diet and feeding method depends on the species, but most catfish are nocturnal, opportunistic omnivores and will eat whatever is available.25

Catfish are known as bottom-feeders due to their tendency to stay close to the bottom of a body of water. According to some sources, catfish that frequently bottom-feed also tend to taste muddy to humans.26 Catfish can scavenge, filter-feed, and actively hunt for food using their highly sophisticated sensory organs, including their sense of smell, barbels, lateral line and external taste receptors.27

Some species only hunt live prey. The flathead catfish, for example, is an ambush predator that primarily hunts smaller fish and crayfish.28Other species are also detritivores, meaning they consume dead matter lying at the bottom of lakes, rivers and other bodies of water.29 There are even wood-eating catfish, although one study suggests that these catfish cannot actually digest or gain energy from the wood they eat.30

Fasting has also been observed among catfish. During winter, black bullhead catfish may stop eating, and one study suggests that Mekong catfish go through fasting periods of up to 30 days and may be able to survive physiologically without food for a year. This may be an adaptation to cope with the wet and dry seasons in the Mekong River, which affect food availability.31

Catfish do not have scales. Some have tough, bony pieces of skin called dermal plates, which appears like armour and provide useful protection against predators.32 Others only have smooth, "naked" skin, similar to an eel’s, covered in mucous and thousands of taste buds.

In the skin mucous of African catfish, scientists have discovered a compound with strong antibacterial properties that protects the fish from infections and could even be used to combat antimicrobial resistance in humans in the future.33

Male denticulate catfish have tiny, bristly teeth called odontodes growing on their dermal plates. These odontodes can regenerate and are used for defence against predators as well as to court females. They have the appearance of stubble and mostly grow around the catfish’s jaw, on the top of its head and its fins.34

The conservation status of catfish ranges all the way from critically endangered to highly abundant and invasive.

The conservation status of catfish ranges all the way from critically endangered to highly abundant and invasive. Invasive species, which are not native to their environments, upset the balance of their host ecosystem.35 The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 191 catfish species as Endangered and 90 as Critically Endangered. However, most catfish species (2,071) are listed as Least Concern.36

The Mekong catfish is one of the world’s most endangered fish species and its population is estimated to have decreased by 90% in the last decade.37 Larger catfish are especially at risk of endangerment due to habitat loss, the building of dams, river pollution and hunting.38 Losing these species would not only be a huge loss for such unique members of our animal kingdom, but would also threaten the ecosystems they live in.

Whilst some catfish are struggling for survival, others are taking over ecosystems. The blue catfish was introduced to Chesapeake Bay – an enormous estuary on the east coast of the US spanning over six states – for recreational fishing, but have since become an invasive species. Invasive species often disturb the food webs and biodiversity of an ecosystem because the native wildlife is not adapted to their presence. Like most catfish, blue catfish are generalist and opportunist feeders, and so create a predator-prey imbalance in Chesapeake Bay.39 The walking catfish, native to Southeast Asia, has become highly invasive in Florida, United States, and its ability to breath air and "walk" on land has greatly accelerated its invasive nature.40 Other invasive catfish species include the Amazon sailfin catfish, invasive in Southeast Asia, and the black bullhead from North America, invasive in Great Britain.41

Catfish lay eggs, but the number of eggs laid and how they are raised varies depending on the species. Both channel and blue catfish lay around 10,000 eggs into a safe area, such as a hole in a mudbank, which are guarded by the males from intruders.42 In some species, including channel catfish, a male might only mate with one female per year during the breeding cycle, despite monogamy being relatively uncommon in fish.43 A Wels catfish – one of the largest catfish species – can lay up to 100,000 eggs in nests underneath tree roots or in aquatic vegetation.44 Eel-tailed catfish, commonly known as freshwater catfish, create very distinctive nests by arranging lots of small rocks in an oval formation on the river bed which the males fiercely guard.45

Some species have more unusual methods. Cuckoo catfish (Synodontis multipunctatus), whose skin resembles that of a leopard, place their eggs into the nests of cichlid fish. Then, the cichlid fish, which carries its own eggs in its mouth to protect them, unknowingly scoops up the catfish's eggs alongside its own offspring. Unfortunately for the cichlids, cuckoo catfish larvae usually hatch earlier and eat the cichlid’s offspring inside its own mouth. This is a reproductive strategy known as brood parasitism, more commonly seen in bird species such as cuckoos – hence the name cuckoo catfish.46

Most catfish are harmless to humans, but around 1,600 species may be venomous.47 Catfish venom glands are associated with the bony spines in front of their dorsal and pictorial fins. Venom is released if the spine punctures another organism.48Most catfish use their venom as a defence mechanism against other fish and the effects of the venom vary depending on the species and the victim. In humans it can cause severe pain and swelling, and people are often at the most risk of infection from the wound. However, a couple of catfish species – the striped eel catfish and the Asian stinging catfish – have a venom so strong it can lead to hospitalisation or even death for humans.49

Do catfish hunt humans? The deaths of three people between 1988 and 2007 in the Kali River, India has been attributed by some locals to the goonch catfish, with eyewitnesses reporting that the victims were dragged down into the water by a creature that looked like an "elongated pig". In the popular British wildlife television series River Monsters, presenter Jeremy Wade succeeded in catching an enormous goonch weighing 75.5kg. However, Wade theorised that a goonch would have to have been much larger to eat a human, and there is little other evidence for goonch aggression towards humans.50 At the other end of the scale, the tiny and transparent candiru, or parasitic catfish, is said to swim up the urethras of people urinating in rivers.51 However, there is no real evidence behind these stories and they remain anecdotal. If anything, catfish generate intriguing folklore, such as Namazu – a giant catfish in Japanese mythology who lives underneath the land and causes earthquakes by thrashing around.52

Catfish, like most fish, have inner ears to detect sound vibrations underwater.53 However, catfish are also part of a group of fish called Otophysi which have a unique hearing adaption. Some have a chain of moveable bones behind the head called the Weberian apparatus (similar to middle ear bones in humans) which connects the inner ear to the swim bladder.54

The swim bladder primarily functions as a buoyancy device in fish, but for Otophysines, it also acts as something akin to an eardrum. The swim bladder wall picks up sound vibrations from the water, which then travel back along the Weberian apparatus to the inner ear. This means otophysan catfish can detect a much broader range of sound frequencies than many other fish, thanks to this adaptation.55

Some catfish also use their sharp hearing as a form of echolocation, emitting short pulses of low-frequency sound to avoid bumping into obstacles in dark and murky water.55 They can rapidly contract the swim bladder muscles to make drumming or pulsing sounds. They can also produce stridulations, which involves rubbing two body parts together to make sounds, similar to what grasshoppers do with their legs.56 Researchers suggest that stridulation – which is a loud and high-frequency sound – is primarily used in distress and to ward off predators, and that the lower frequency drumming sounds may be used to communicate with other catfish of the same species.57

Featured image © Milos Prelevic | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Laura Espana | Unsplash

Quick Facts:

1. University of Michigan. n.d. “Siluriformes.” Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology. Accessed Aug 13, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Siluriformes/classification/.

2. “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

Fact File:

1. Dunham, Rex A. Elaswad, Ahmed. 2018. “Catfish Biology and Farming.” Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 6: 305-325. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-030117-014646.

2. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e2008; “Mekong Giant Catfish.” WWF. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/wildlife_practice/profiles/fish_marine/giant_catfish/; “Walking Catfish (Clarius batrachus): Ecological Risk Screening Summary.” Web Version 2018. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Walking-Catfish.pdf.

3. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

4. Santhanam, Ramasamy. 2024. “Biology and Ecology of the Venomous Catfishes.” United States: Apple Academic Press.

5. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

6. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081.

7. Duponchelle, Fabrice et al. 2016. “Trans-Amazonian natal homing in giant catfish.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 53(5), pp. 1511-1520. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12665.

8. Caprio, J. 1993. “The taste system of the channel catfish: from biophysics to behavior.” Trends Neurosci. 16(5), pp. 192-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(93)90152-c.

9. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751.

10. Geeringckx, Tom. 2012. “Soft Dentin Results in Unique Flexible Teeth in Scraping Catfishes.” 85(5). https://doi.org/10.1086/667532.

11. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081.

12. Ikeya, Koki. Kume, Manabu. 2024. “Thirteen-year monitoring reveals that Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) has an annual feeding rhythm and a prolonged fasting period.” Ichthyological Research. 71, pp. 378-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-023-00944-y.

13. University of Michigan. n.d. “Siluriformes.” Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology. Accessed Aug 13, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Siluriformes/classification/; “All Catfish Families.” PlanetCatfish. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.planetcatfish.com/common/families.php; “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

14. “All Catfish Families.” PlanetCatfish. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.planetcatfish.com/common/families.php; De Souza da Costa e Silva, Gabriel. Fernandes Roxo, Fábio. Oilveria, Claudio. 2013. “Pareiorhina hyptiorhachis, a new catfish species from Rio Paraíba do Sul basin, southeastern Brazil (Siluriformes, Loricariidae).” ZooKeys 315: 65-76. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.315.5307.

15. Hogam, Zeb S. 2011. “Ecology and Conservation of Large-Bodied Freshwater Catfish: A Global Perspective.” American Fisheries Society Symposium. 77: 39-53. http://aquaticecosystemslab.org/publications/039-054%20hogan.pdf.

16. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

17. Welzel, Georg. Schuster, Stefan. 2021. “Efficient high-voltage protection in the electric catfish.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 224(4). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.239855.

18. Caprio, John et al. 2014. “Marine teleost locates live prey through pH sensing.” Science. 344(6188): 1154-1156. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1252697.

19. “Order Summary for Siluriformes.” 2009. FishBase. https://fishbase.se/summary/OrdersSummary.php?order=Siluriformes.

20. Rossi, Giulia. 2023. “Catfish give ‘holding your breath’ a whole new meaning.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 226(23). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.245038.

21. Pineda, Mar. et al. 2020. “Social dynamics obscure the effect of temperature on air breathing in Corydoras catfish.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 223(21). https://doi.org/10.1242%2Fjeb.222133.

22. Bressman, Noah R. Hill, Jeffrey E. Ashley-Ross, Miriam A. 2020. “Why did the invasive walking catfish cross the road? Terrestrial chemoreception described for the first time in a fish.” Journal of Fish Biology. 97(3): 895-907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14465.

23. Bressman, Noah R. Morrison, Callen H. Ashley-Ross, Miriam A. 2021. “Reffling: A Novel Locomotor Behavior Used by Neotropical Armored Catfishes (Loricariidae) in Terrestrial Environments.” BioOne. 109(2): 608-625. https://doi.org/10.1643/i2020084.

24. Maie, Takashi. 2024. “Climbing waterfalls - Muscle and movement.” Encyclopaedia of Fish Physiology (Second Edition), pp. 636-648. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90801-6.00098-7; American Museum of natural History. 2009. “Fish Out Of Water: New Species of Climbing Fish from Remote Venezuela Shakes the Catfish Family Tree.” ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090121122947.htm.

25. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081; “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish; “North African catfish - Natural food and feeding habits.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fao.org/fishery/affris/species-profiles/north-african-catfish/natural-food-and-feeding-habits/en/.

26. “Blue Catfish: Invasive and Delicious.” 2020. NOAA Fisheries. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/blue-catfish-invasive-and-delicious/.

27. “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish; “North African catfish - Natural food and feeding habits.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fao.org/fishery/affris/species-profiles/north-african-catfish/natural-food-and-feeding-habits/en/.

28. “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish.

29. German, Donovan P et al. 2010. “Feast to famine: The effects of food quality and quantity on the gut structure and function of a detritivorous catfish (Teleostei: Loricariidae).” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 155(3), pp. 281-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.018.

30. German, D.P. “Inside the guts of wood-eating catfishes: can they digest wood?” 2009. J Comp Physiol B 179, pp. 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-009-0381-1.

31. Ikeya, Koki. Kume, Manabu. 2024. “Thirteen-year monitoring reveals that Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) has an annual feeding rhythm and a prolonged fasting period.” Ichthyological Research. 71, pp. 378-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-023-00944-y.

32. Ebenstein, Donna et al. 2015. “Characterization of dermal plates from armored catfish Pterygoplichthys pardalis reveals sandwich-like nanocomposite structure.” Journal of the Mechanical Behaviour of Biomedical Materials. 45, pp. 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.02.002.

33. Johnson, Anne Frances. 2024. “Catfish skin mucus yields promising antibacterial compound.” AS BMB Today. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.asbmb.org/asbmb-today/science/032424/catfish-skin-mucus-yields-antibacterial-compound#:~:text=Scientists%20extracted%20a%20compound%20with,Discover%20BMB%20in%20San%20Antonio.

34. Montoya-Burgos, Juan. 2017. “When teeth grow on the body.” Université de Genève. https://www.unige.ch/medias/en/2017/lorsque-les-dents-poussent-sur-le-corps.

35. Pavid, Katie. 2024. “What are invasive species?” Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-are-invasive-species.html

36. “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

37. “Mekong Giant Catfish.” WWF. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/wildlife_practice/profiles/fish_marine/giant_catfish/.

38. Hogam, Zeb S. 2011. “Ecology and Conservation of Large-Bodied Freshwater Catfish: A Global Perspective.” American Fisheries Society Symposium. 77: 39-53. http://aquaticecosystemslab.org/publications/039-054%20hogan.pdf.

39. Fabrizio, Mary C. Nepal, Vaskar. Tuckey, Troy D. 2020. “Invasive Blue Catfish in the Chesapeake Bay Region: A Case Study of Competing Management Objectives.” North American Journal of Fisheries management. 41(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/nafm.10552.

40. “Walking Catfish (Clarius batrachus): Ecological Risk Screening Summary.” Web Version 2018. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Walking-Catfish.pdf.

41. Chaichana, Ratcha. Johgphadungkiet, Sirapat. 2012. “Assessment of the invasive catfish Pterygoplichthys paradalis (Castelnau, 1855) in Thailand: ecological impacts and biological control alternatives.” Tropical Zoology. 25(4), pp.173-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/03946975.2012.738494; Environment Agency. 2022. “Managing the risk from non-native fish.” Gov.UK. Fisheries and biodiversity. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2022/05/30/managing-the-risk-from-non-native-fish/.

42. “Catfish, Channel.” Oklahoma Department of Wildlife. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/wildlife/field-guide/fish/catfish-channel; “Catfish, Blue.” Oklahoma Department of Wildlife. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/wildlife/field-guide/fish/catfish-blue

43. Tatarenkov, Andrey et al. 2006. “Genetic Monogamy in the Channel Catfish, Ictalurus Punctatus, a Species with Uniparental Nest Guarding.” Copeia, 4: 735-741. 10.1643/0045-8511(2006)6[735:GMITCC]2.0.CO;2

44. “Wels Catfish.” Catfish Conservation Group. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.catfishconservationgroup.co.uk/welscatfish/

45. “Freshwater catfish at Tahbilk Lagoon: Breeding, spawning and water levels.” Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research. 2025. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.ari.vic.gov.au/research/threatened-plants-and-animals/freshwater-catfish-at-tahbilk-lagoon

46. Meyer, Alex. 2018. “Brood parasitism in fish.” University of Konstanz. Accessed Aug 14 2024. https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/536641.

47. Santhanam, Ramasamy. 2024. “Biology and Ecology of the Venomous Catfishes.” United States: Apple Academic Press; Ross-Flanigan, Nancy. 2009. “Killer catfish? Venomous species surprisingly common, study finds.” Michigan News: University of Michigan. Accessed Aug 14 2024. https://news.umich.edu/killer-catfish-venomous-species-surprisingly-common-study-finds/.

48. Wright, Jeremy J. 2012. “Adaptive significance of venom glands in the tadpole madtom Noturus gyrinus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae).”Journal of Experimental Biology. 215(11): 1816-1823. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.068361.

49. Wright, Jeremy J. 2009. “Diversity, phylogenetic distribution, and origins of venomous catfishes.” BMC Ecology and Evolution. 9. https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2148-9-282.

50. River Monsters. 2019. “Catching a monster Goonch catfish | CATFISH | River Monsters.” Accessed Aug 14, 2024. youtube.com/watch?v=F2Zh3JzfyJU; Howard, Jaden. 2019. “Fish biology and Fisheries.” Scientific e-Resources.

51. “Order Summary for Siluriformes.” 2009. FishBase. https://fishbase.se/summary/OrdersSummary.php?order=Siluriformes.

52. “Namazu - The Ancient History Behind the Earthquake Causing Catfish.” Sabukaru. Accessed Feb 20, 2025. https://sabukaru.online/articles/namazu-the-ancient-history-behind-the-earthquake-causing-catfish

53. “How do fish hear?” Ocean Conservation Research. Accessed Aug 14, 2024. https://ocr.org/learn/how-fish-hear/.

54. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751;Ladich, Friedrich. 2024. “Diversity of sound production and hearing in fishes: Exploring the riddles of communication and sensory biology.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 155(1). https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0024243

55. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751.

56. Parmentier, E. et al. 2010. “Functional study of the pectoral spine stridulation mechanism in different mochokid catfishes.” Journal of Experimental Biology. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.039461.

57. Ghahramani, Zachary N. Mohajer, Yasha. Fine, Michael L. 2014. “Developmental variation in sound production in water and air in the blue catfish Ictalurus furcatus.” Journal of Experimental Biology 217(23): 4244-4251. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.112946; Knight, Lisa. Ladich, Friedrich. 2024. “Distress sounds of thorny catfishes emitted underwater and in air: characteristics and potential significance.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 217(22): 4068-4078. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.110957

With thousands of species and countless individuals, catfish are among the most abundant and adaptable freshwater fish on Earth. These remarkable creatures don’t just swim – they can walk on land, climb walls, and even breathe air, making them one of the most surprising fish in nature.

Fry

School, shoal

Larger fish, other catfish, wading birds, turtles, human

5-70 depending on species and wild/captive status

1.2cm to 5m, which is almost as long as a giraffe is tall

The heaviest catfish can weigh up to 100kg, which is similar to a standard refrigerator in the UK

Worldwide in fresh, brackish and marine water

Unknown

Least Concern – Critically Endangered

Nearly all catfish have barbels – whisker-like protrusions from their jaw and chin – which is a sensory organ that helps them taste and feel.

Catfish can be characterised by their wide, fleshy lips, sausage-like bodies and whiskery faces which give them their name. The abundance of some catfish species and unusual looks of others make them a popular target for sport fishers and aquarium enthusiasts.1 Most catfish are bottom dwellers, meaning they sweep along the bottom of rivers, lakes, estuaries and other bodies of freshwater. Catfish belong to one of the largest orders of fish. This diverse group contains both critically endangered species, such as the Mekong giant catfish, primarily found in the Mekong River basin in Southeast Asia, and highly invasive species, such as the walking catfish, which has established itself in Florida.2

There are between 34 and 44 families of catfish and at least 3,400 different species, depending on taxonomic classification.13 Some of the smallest catfish include the pygmy corydoras, which are popular aquarium additions and measure 3cm head to tail; the Pareiorhina hyptiorhachis, native to fast-flowing little streams in South America which measure approximately 3-3.5cm in length; and the shiny, eel-like candiru catfish which can be as small as 1.2cm.14 The Mekong giant catfish and Goonch catfish, both found in the Mekong river, are the heaviest species and can weigh over 100kg, whilst the Wels catfish found in European waters is the longest, reaching a maximum length of 5m. The piraiba in the Amazon can grow to 4m. Large catfish usually migrate huge distances and create ecological links between parts of a river miles apart.15

Suckermouth catfish are also known as algae-eaters for their tendency to latch onto the glass walls of aquariums and fastidiously consume algae.16 Long-whiskered catfish have particularly long barbels trailing from their snout. All catfish are extremely sensitive to their environments, but some have developed truly fascinating abilities: electric catfish can discharge up to 350 volts and are seemingly immune to high shocks themselves.17 Japanese sea catfish can detect the minute changes in water pH that sea worms create by exhaling carbon dioxide to help them locate prey.18

Catfish, like other fish, take in oxygen through their gills. However, there is one family within the Siluriformes order known as "airbreathing catfish" (Clariidae), which, as the name suggests, can swim up to the surface and gulp in air.19 They have evolved this ability to cope with hypoxic (low oxygen) environments. The striped catfish for example, lives in heavily polluted waterways in Southeast Asia, where the oxygen levels in the water are very low.20 To survive, it must surface for air which then diffuses into the blood. In the airbreathing corydoras catfish, there is a phenomenon of group airbreathing, which helps reduce vulnerability to predators.21

The catfish's capacity to adapt does not end there; its airbreathing abilities have allowed some to become fish out of water. The walking catfish, another airbreathing species, sometimes resembles a dark, bloated slug and can survive for 18 hours, moving up to 1.2km on land.22 Much like slugs, the walking catfish is often seen after periods of rain or flooding. Their long and sweeping barbels help them navigate both water and land. In 2021 scientists coined a new term – "reffling" – after studying the movement of the armoured suckermouth catfish which uses its mouth, tail and a "grasping" pelvic fin to haul itself across dry ground.23 They can last up to 30 hours out of water, provided a layer of mucus keeps them moist. Similarly, some catfish have a climbing style known as "inching", where they alternate between using suction from their mouths and their pelvic disc to shuffle up vertical cave walls.24

The catfish’s diet includes fish, molluscs, algae, plants, phytoplankton, fish eggs, and even other catfish. Both diet and feeding method depends on the species, but most catfish are nocturnal, opportunistic omnivores and will eat whatever is available.25

Catfish are known as bottom-feeders due to their tendency to stay close to the bottom of a body of water. According to some sources, catfish that frequently bottom-feed also tend to taste muddy to humans.26 Catfish can scavenge, filter-feed, and actively hunt for food using their highly sophisticated sensory organs, including their sense of smell, barbels, lateral line and external taste receptors.27

Some species only hunt live prey. The flathead catfish, for example, is an ambush predator that primarily hunts smaller fish and crayfish.28Other species are also detritivores, meaning they consume dead matter lying at the bottom of lakes, rivers and other bodies of water.29 There are even wood-eating catfish, although one study suggests that these catfish cannot actually digest or gain energy from the wood they eat.30

Fasting has also been observed among catfish. During winter, black bullhead catfish may stop eating, and one study suggests that Mekong catfish go through fasting periods of up to 30 days and may be able to survive physiologically without food for a year. This may be an adaptation to cope with the wet and dry seasons in the Mekong River, which affect food availability.31

Catfish do not have scales. Some have tough, bony pieces of skin called dermal plates, which appears like armour and provide useful protection against predators.32 Others only have smooth, "naked" skin, similar to an eel’s, covered in mucous and thousands of taste buds.

In the skin mucous of African catfish, scientists have discovered a compound with strong antibacterial properties that protects the fish from infections and could even be used to combat antimicrobial resistance in humans in the future.33

Male denticulate catfish have tiny, bristly teeth called odontodes growing on their dermal plates. These odontodes can regenerate and are used for defence against predators as well as to court females. They have the appearance of stubble and mostly grow around the catfish’s jaw, on the top of its head and its fins.34

The conservation status of catfish ranges all the way from critically endangered to highly abundant and invasive.

The conservation status of catfish ranges all the way from critically endangered to highly abundant and invasive. Invasive species, which are not native to their environments, upset the balance of their host ecosystem.35 The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 191 catfish species as Endangered and 90 as Critically Endangered. However, most catfish species (2,071) are listed as Least Concern.36

The Mekong catfish is one of the world’s most endangered fish species and its population is estimated to have decreased by 90% in the last decade.37 Larger catfish are especially at risk of endangerment due to habitat loss, the building of dams, river pollution and hunting.38 Losing these species would not only be a huge loss for such unique members of our animal kingdom, but would also threaten the ecosystems they live in.

Whilst some catfish are struggling for survival, others are taking over ecosystems. The blue catfish was introduced to Chesapeake Bay – an enormous estuary on the east coast of the US spanning over six states – for recreational fishing, but have since become an invasive species. Invasive species often disturb the food webs and biodiversity of an ecosystem because the native wildlife is not adapted to their presence. Like most catfish, blue catfish are generalist and opportunist feeders, and so create a predator-prey imbalance in Chesapeake Bay.39 The walking catfish, native to Southeast Asia, has become highly invasive in Florida, United States, and its ability to breath air and "walk" on land has greatly accelerated its invasive nature.40 Other invasive catfish species include the Amazon sailfin catfish, invasive in Southeast Asia, and the black bullhead from North America, invasive in Great Britain.41

Catfish lay eggs, but the number of eggs laid and how they are raised varies depending on the species. Both channel and blue catfish lay around 10,000 eggs into a safe area, such as a hole in a mudbank, which are guarded by the males from intruders.42 In some species, including channel catfish, a male might only mate with one female per year during the breeding cycle, despite monogamy being relatively uncommon in fish.43 A Wels catfish – one of the largest catfish species – can lay up to 100,000 eggs in nests underneath tree roots or in aquatic vegetation.44 Eel-tailed catfish, commonly known as freshwater catfish, create very distinctive nests by arranging lots of small rocks in an oval formation on the river bed which the males fiercely guard.45

Some species have more unusual methods. Cuckoo catfish (Synodontis multipunctatus), whose skin resembles that of a leopard, place their eggs into the nests of cichlid fish. Then, the cichlid fish, which carries its own eggs in its mouth to protect them, unknowingly scoops up the catfish's eggs alongside its own offspring. Unfortunately for the cichlids, cuckoo catfish larvae usually hatch earlier and eat the cichlid’s offspring inside its own mouth. This is a reproductive strategy known as brood parasitism, more commonly seen in bird species such as cuckoos – hence the name cuckoo catfish.46

Most catfish are harmless to humans, but around 1,600 species may be venomous.47 Catfish venom glands are associated with the bony spines in front of their dorsal and pictorial fins. Venom is released if the spine punctures another organism.48Most catfish use their venom as a defence mechanism against other fish and the effects of the venom vary depending on the species and the victim. In humans it can cause severe pain and swelling, and people are often at the most risk of infection from the wound. However, a couple of catfish species – the striped eel catfish and the Asian stinging catfish – have a venom so strong it can lead to hospitalisation or even death for humans.49

Do catfish hunt humans? The deaths of three people between 1988 and 2007 in the Kali River, India has been attributed by some locals to the goonch catfish, with eyewitnesses reporting that the victims were dragged down into the water by a creature that looked like an "elongated pig". In the popular British wildlife television series River Monsters, presenter Jeremy Wade succeeded in catching an enormous goonch weighing 75.5kg. However, Wade theorised that a goonch would have to have been much larger to eat a human, and there is little other evidence for goonch aggression towards humans.50 At the other end of the scale, the tiny and transparent candiru, or parasitic catfish, is said to swim up the urethras of people urinating in rivers.51 However, there is no real evidence behind these stories and they remain anecdotal. If anything, catfish generate intriguing folklore, such as Namazu – a giant catfish in Japanese mythology who lives underneath the land and causes earthquakes by thrashing around.52

Catfish, like most fish, have inner ears to detect sound vibrations underwater.53 However, catfish are also part of a group of fish called Otophysi which have a unique hearing adaption. Some have a chain of moveable bones behind the head called the Weberian apparatus (similar to middle ear bones in humans) which connects the inner ear to the swim bladder.54

The swim bladder primarily functions as a buoyancy device in fish, but for Otophysines, it also acts as something akin to an eardrum. The swim bladder wall picks up sound vibrations from the water, which then travel back along the Weberian apparatus to the inner ear. This means otophysan catfish can detect a much broader range of sound frequencies than many other fish, thanks to this adaptation.55

Some catfish also use their sharp hearing as a form of echolocation, emitting short pulses of low-frequency sound to avoid bumping into obstacles in dark and murky water.55 They can rapidly contract the swim bladder muscles to make drumming or pulsing sounds. They can also produce stridulations, which involves rubbing two body parts together to make sounds, similar to what grasshoppers do with their legs.56 Researchers suggest that stridulation – which is a loud and high-frequency sound – is primarily used in distress and to ward off predators, and that the lower frequency drumming sounds may be used to communicate with other catfish of the same species.57

Featured image © Milos Prelevic | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Laura Espana | Unsplash

Quick Facts:

1. University of Michigan. n.d. “Siluriformes.” Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology. Accessed Aug 13, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Siluriformes/classification/.

2. “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

Fact File:

1. Dunham, Rex A. Elaswad, Ahmed. 2018. “Catfish Biology and Farming.” Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 6: 305-325. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-030117-014646.

2. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e2008; “Mekong Giant Catfish.” WWF. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/wildlife_practice/profiles/fish_marine/giant_catfish/; “Walking Catfish (Clarius batrachus): Ecological Risk Screening Summary.” Web Version 2018. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Walking-Catfish.pdf.

3. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

4. Santhanam, Ramasamy. 2024. “Biology and Ecology of the Venomous Catfishes.” United States: Apple Academic Press.

5. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

6. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081.

7. Duponchelle, Fabrice et al. 2016. “Trans-Amazonian natal homing in giant catfish.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 53(5), pp. 1511-1520. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12665.

8. Caprio, J. 1993. “The taste system of the channel catfish: from biophysics to behavior.” Trends Neurosci. 16(5), pp. 192-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(93)90152-c.

9. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751.

10. Geeringckx, Tom. 2012. “Soft Dentin Results in Unique Flexible Teeth in Scraping Catfishes.” 85(5). https://doi.org/10.1086/667532.

11. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081.

12. Ikeya, Koki. Kume, Manabu. 2024. “Thirteen-year monitoring reveals that Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) has an annual feeding rhythm and a prolonged fasting period.” Ichthyological Research. 71, pp. 378-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-023-00944-y.

13. University of Michigan. n.d. “Siluriformes.” Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology. Accessed Aug 13, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Siluriformes/classification/; “All Catfish Families.” PlanetCatfish. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.planetcatfish.com/common/families.php; “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

14. “All Catfish Families.” PlanetCatfish. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.planetcatfish.com/common/families.php; De Souza da Costa e Silva, Gabriel. Fernandes Roxo, Fábio. Oilveria, Claudio. 2013. “Pareiorhina hyptiorhachis, a new catfish species from Rio Paraíba do Sul basin, southeastern Brazil (Siluriformes, Loricariidae).” ZooKeys 315: 65-76. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.315.5307.

15. Hogam, Zeb S. 2011. “Ecology and Conservation of Large-Bodied Freshwater Catfish: A Global Perspective.” American Fisheries Society Symposium. 77: 39-53. http://aquaticecosystemslab.org/publications/039-054%20hogan.pdf.

16. NeSmith, Richard A. 2021 “Catfish: Bottom-Dwellers.” Applied principles of Education and Learning.

17. Welzel, Georg. Schuster, Stefan. 2021. “Efficient high-voltage protection in the electric catfish.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 224(4). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.239855.

18. Caprio, John et al. 2014. “Marine teleost locates live prey through pH sensing.” Science. 344(6188): 1154-1156. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1252697.

19. “Order Summary for Siluriformes.” 2009. FishBase. https://fishbase.se/summary/OrdersSummary.php?order=Siluriformes.

20. Rossi, Giulia. 2023. “Catfish give ‘holding your breath’ a whole new meaning.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 226(23). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.245038.

21. Pineda, Mar. et al. 2020. “Social dynamics obscure the effect of temperature on air breathing in Corydoras catfish.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 223(21). https://doi.org/10.1242%2Fjeb.222133.

22. Bressman, Noah R. Hill, Jeffrey E. Ashley-Ross, Miriam A. 2020. “Why did the invasive walking catfish cross the road? Terrestrial chemoreception described for the first time in a fish.” Journal of Fish Biology. 97(3): 895-907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14465.

23. Bressman, Noah R. Morrison, Callen H. Ashley-Ross, Miriam A. 2021. “Reffling: A Novel Locomotor Behavior Used by Neotropical Armored Catfishes (Loricariidae) in Terrestrial Environments.” BioOne. 109(2): 608-625. https://doi.org/10.1643/i2020084.

24. Maie, Takashi. 2024. “Climbing waterfalls - Muscle and movement.” Encyclopaedia of Fish Physiology (Second Edition), pp. 636-648. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90801-6.00098-7; American Museum of natural History. 2009. “Fish Out Of Water: New Species of Climbing Fish from Remote Venezuela Shakes the Catfish Family Tree.” ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090121122947.htm.

25. Segaran, Thirukanthan Chandra et al. 2023. “Catfishes: A global review of the literature.” Heliyon 9(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20081; “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish; “North African catfish - Natural food and feeding habits.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fao.org/fishery/affris/species-profiles/north-african-catfish/natural-food-and-feeding-habits/en/.

26. “Blue Catfish: Invasive and Delicious.” 2020. NOAA Fisheries. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/blue-catfish-invasive-and-delicious/.

27. “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish; “North African catfish - Natural food and feeding habits.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fao.org/fishery/affris/species-profiles/north-african-catfish/natural-food-and-feeding-habits/en/.

28. “Catfish and bullheads.” Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/fish-species/catfish.

29. German, Donovan P et al. 2010. “Feast to famine: The effects of food quality and quantity on the gut structure and function of a detritivorous catfish (Teleostei: Loricariidae).” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 155(3), pp. 281-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.018.

30. German, D.P. “Inside the guts of wood-eating catfishes: can they digest wood?” 2009. J Comp Physiol B 179, pp. 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-009-0381-1.

31. Ikeya, Koki. Kume, Manabu. 2024. “Thirteen-year monitoring reveals that Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) has an annual feeding rhythm and a prolonged fasting period.” Ichthyological Research. 71, pp. 378-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-023-00944-y.

32. Ebenstein, Donna et al. 2015. “Characterization of dermal plates from armored catfish Pterygoplichthys pardalis reveals sandwich-like nanocomposite structure.” Journal of the Mechanical Behaviour of Biomedical Materials. 45, pp. 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.02.002.

33. Johnson, Anne Frances. 2024. “Catfish skin mucus yields promising antibacterial compound.” AS BMB Today. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.asbmb.org/asbmb-today/science/032424/catfish-skin-mucus-yields-antibacterial-compound#:~:text=Scientists%20extracted%20a%20compound%20with,Discover%20BMB%20in%20San%20Antonio.

34. Montoya-Burgos, Juan. 2017. “When teeth grow on the body.” Université de Genève. https://www.unige.ch/medias/en/2017/lorsque-les-dents-poussent-sur-le-corps.

35. Pavid, Katie. 2024. “What are invasive species?” Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-are-invasive-species.html

36. “Red list.” IUCN. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

37. “Mekong Giant Catfish.” WWF. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/wildlife_practice/profiles/fish_marine/giant_catfish/.

38. Hogam, Zeb S. 2011. “Ecology and Conservation of Large-Bodied Freshwater Catfish: A Global Perspective.” American Fisheries Society Symposium. 77: 39-53. http://aquaticecosystemslab.org/publications/039-054%20hogan.pdf.

39. Fabrizio, Mary C. Nepal, Vaskar. Tuckey, Troy D. 2020. “Invasive Blue Catfish in the Chesapeake Bay Region: A Case Study of Competing Management Objectives.” North American Journal of Fisheries management. 41(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/nafm.10552.

40. “Walking Catfish (Clarius batrachus): Ecological Risk Screening Summary.” Web Version 2018. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Walking-Catfish.pdf.

41. Chaichana, Ratcha. Johgphadungkiet, Sirapat. 2012. “Assessment of the invasive catfish Pterygoplichthys paradalis (Castelnau, 1855) in Thailand: ecological impacts and biological control alternatives.” Tropical Zoology. 25(4), pp.173-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/03946975.2012.738494; Environment Agency. 2022. “Managing the risk from non-native fish.” Gov.UK. Fisheries and biodiversity. Accessed 20 Sept 2024. https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2022/05/30/managing-the-risk-from-non-native-fish/.

42. “Catfish, Channel.” Oklahoma Department of Wildlife. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/wildlife/field-guide/fish/catfish-channel; “Catfish, Blue.” Oklahoma Department of Wildlife. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/wildlife/field-guide/fish/catfish-blue

43. Tatarenkov, Andrey et al. 2006. “Genetic Monogamy in the Channel Catfish, Ictalurus Punctatus, a Species with Uniparental Nest Guarding.” Copeia, 4: 735-741. 10.1643/0045-8511(2006)6[735:GMITCC]2.0.CO;2

44. “Wels Catfish.” Catfish Conservation Group. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.catfishconservationgroup.co.uk/welscatfish/

45. “Freshwater catfish at Tahbilk Lagoon: Breeding, spawning and water levels.” Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research. 2025. Accessed 20 Feb, 2025. https://www.ari.vic.gov.au/research/threatened-plants-and-animals/freshwater-catfish-at-tahbilk-lagoon

46. Meyer, Alex. 2018. “Brood parasitism in fish.” University of Konstanz. Accessed Aug 14 2024. https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/536641.

47. Santhanam, Ramasamy. 2024. “Biology and Ecology of the Venomous Catfishes.” United States: Apple Academic Press; Ross-Flanigan, Nancy. 2009. “Killer catfish? Venomous species surprisingly common, study finds.” Michigan News: University of Michigan. Accessed Aug 14 2024. https://news.umich.edu/killer-catfish-venomous-species-surprisingly-common-study-finds/.

48. Wright, Jeremy J. 2012. “Adaptive significance of venom glands in the tadpole madtom Noturus gyrinus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae).”Journal of Experimental Biology. 215(11): 1816-1823. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.068361.

49. Wright, Jeremy J. 2009. “Diversity, phylogenetic distribution, and origins of venomous catfishes.” BMC Ecology and Evolution. 9. https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2148-9-282.

50. River Monsters. 2019. “Catching a monster Goonch catfish | CATFISH | River Monsters.” Accessed Aug 14, 2024. youtube.com/watch?v=F2Zh3JzfyJU; Howard, Jaden. 2019. “Fish biology and Fisheries.” Scientific e-Resources.

51. “Order Summary for Siluriformes.” 2009. FishBase. https://fishbase.se/summary/OrdersSummary.php?order=Siluriformes.

52. “Namazu - The Ancient History Behind the Earthquake Causing Catfish.” Sabukaru. Accessed Feb 20, 2025. https://sabukaru.online/articles/namazu-the-ancient-history-behind-the-earthquake-causing-catfish

53. “How do fish hear?” Ocean Conservation Research. Accessed Aug 14, 2024. https://ocr.org/learn/how-fish-hear/.

54. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751;Ladich, Friedrich. 2024. “Diversity of sound production and hearing in fishes: Exploring the riddles of communication and sensory biology.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 155(1). https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0024243

55. Ladich, Friedrich. 2023. “Hearing in catfishes: 200 years of research.” Fish and Fisheries. 24(4): 618-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12751.

56. Parmentier, E. et al. 2010. “Functional study of the pectoral spine stridulation mechanism in different mochokid catfishes.” Journal of Experimental Biology. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.039461.

57. Ghahramani, Zachary N. Mohajer, Yasha. Fine, Michael L. 2014. “Developmental variation in sound production in water and air in the blue catfish Ictalurus furcatus.” Journal of Experimental Biology 217(23): 4244-4251. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.112946; Knight, Lisa. Ladich, Friedrich. 2024. “Distress sounds of thorny catfishes emitted underwater and in air: characteristics and potential significance.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 217(22): 4068-4078. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.110957

Fry

School, shoal

Larger fish, other catfish, wading birds, turtles, human

5-70 depending on species and wild/captive status

1.2cm to 5m, which is almost as long as a giraffe is tall

The heaviest catfish can weigh up to 100kg, which is similar to a standard refrigerator in the UK

Worldwide in fresh, brackish and marine water

Unknown

Least Concern – Critically Endangered

Nearly all catfish have barbels – whisker-like protrusions from their jaw and chin – which is a sensory organ that helps them taste and feel.