BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

With some measuring as small as a human thumb, these lightning-fast birds are named after the “humming” sound their wings make as they beat at over 3,000 times a minute. Hummingbirds can fly forwards and backwards, and even hover in mid-air like tiny helicopters. These miniscule birds have such high metabolisms that to survive they must consume a colossal volume of nectar, equivalent in human terms to around 300 pounds in weight of hamburgers a day.

Hummingbirds can fly forwards and backwards, and even hover in mid-air like tiny helicopters.

Hummingbirds are lightning-fast tiny birds with eye-catching, colourful feathers that make them dazzle like jewels in the sun. With some having bodies as small as your thumb, hummingbirds beat their wings an average of 3,000 times per minute in a figure of eight pattern that creates lift on both the up and down strokes.10 Some hummingbirds can fly at speeds of over 33 miles per hour.11

They can hover in mid-air, fly upside down and backwards, and turn on a hairpin, displaying incredible acrobatic prowess. They are also the world’s smallest migratory bird, with some species flying upwards of 4,000 miles to reach their breeding grounds.12

There are approximately 366 species of hummingbirds. The most well-known species in the US is the ruby-throated hummingbird, which spends its winter in Mexico and Central America, before embarking on a marathon journey across the Gulf of Mexico to breed in Northern America – although some are known to fly around the Gulf of Mexico instead.13Some animals complete the journey in one non-stop flight. Rufous hummingbirds also complete a long migratory journey. For example, one rufous hummingbird was tracked more than 3,500 miles travelling from Florida to Alaska.14 The longest recorded migration of any hummingbird—a 5,200-mile round trip between the Chilean coast and the Peruvian Andes – meanwhile, can be attributed to the southern giant hummingbird.15

Other notable species common to the US include the black-chinned hummingbird – found in mountain forests, deserts, urban parks and woodlands – and the broad-tailed hummingbird, one of the noisiest hummingbirds thanks to the loud metallic trill that males produce with their wings. Allen’s hummingbirds, Costa’s hummingbirds and buff-bellied hummingbirds are also commonly seen in North America.

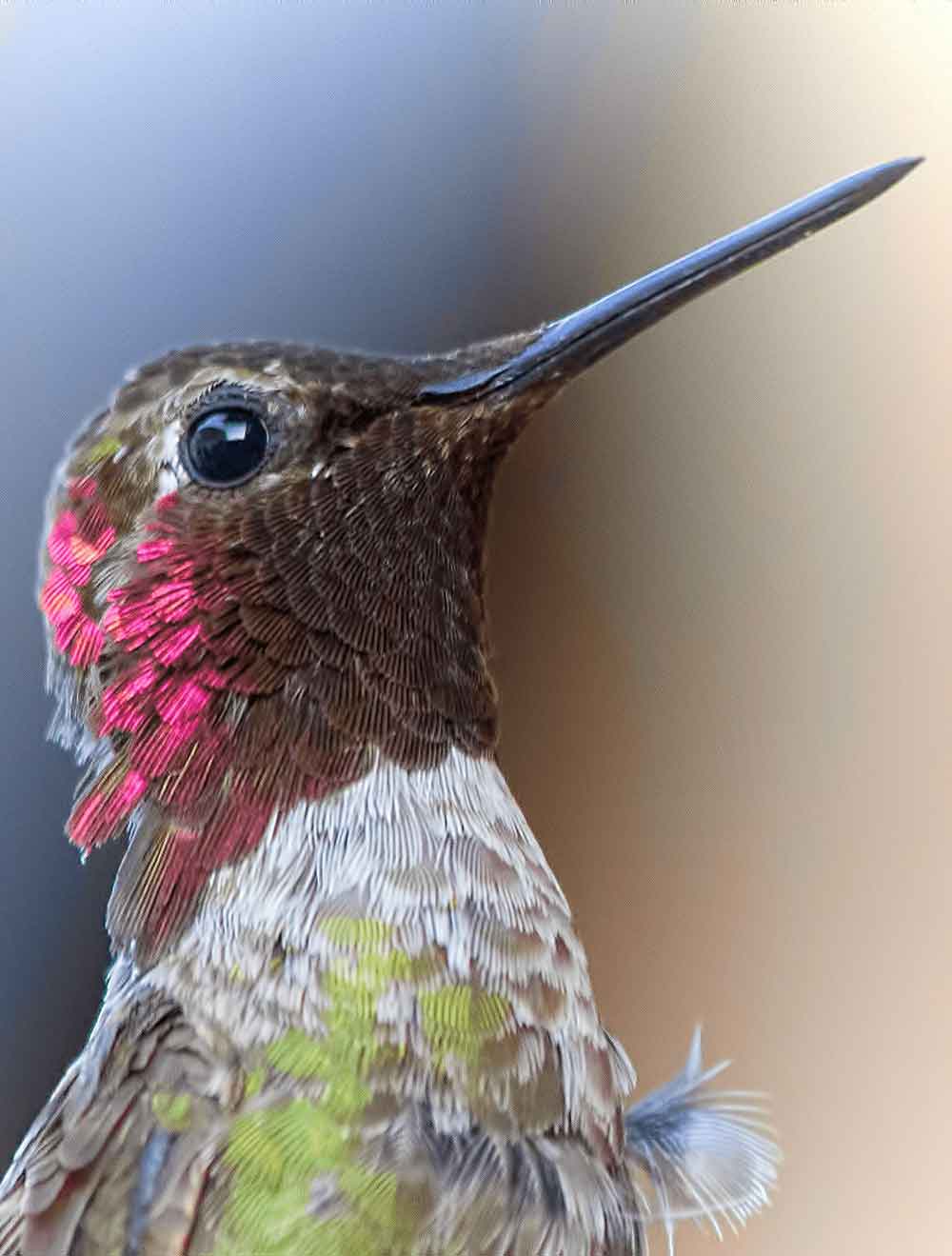

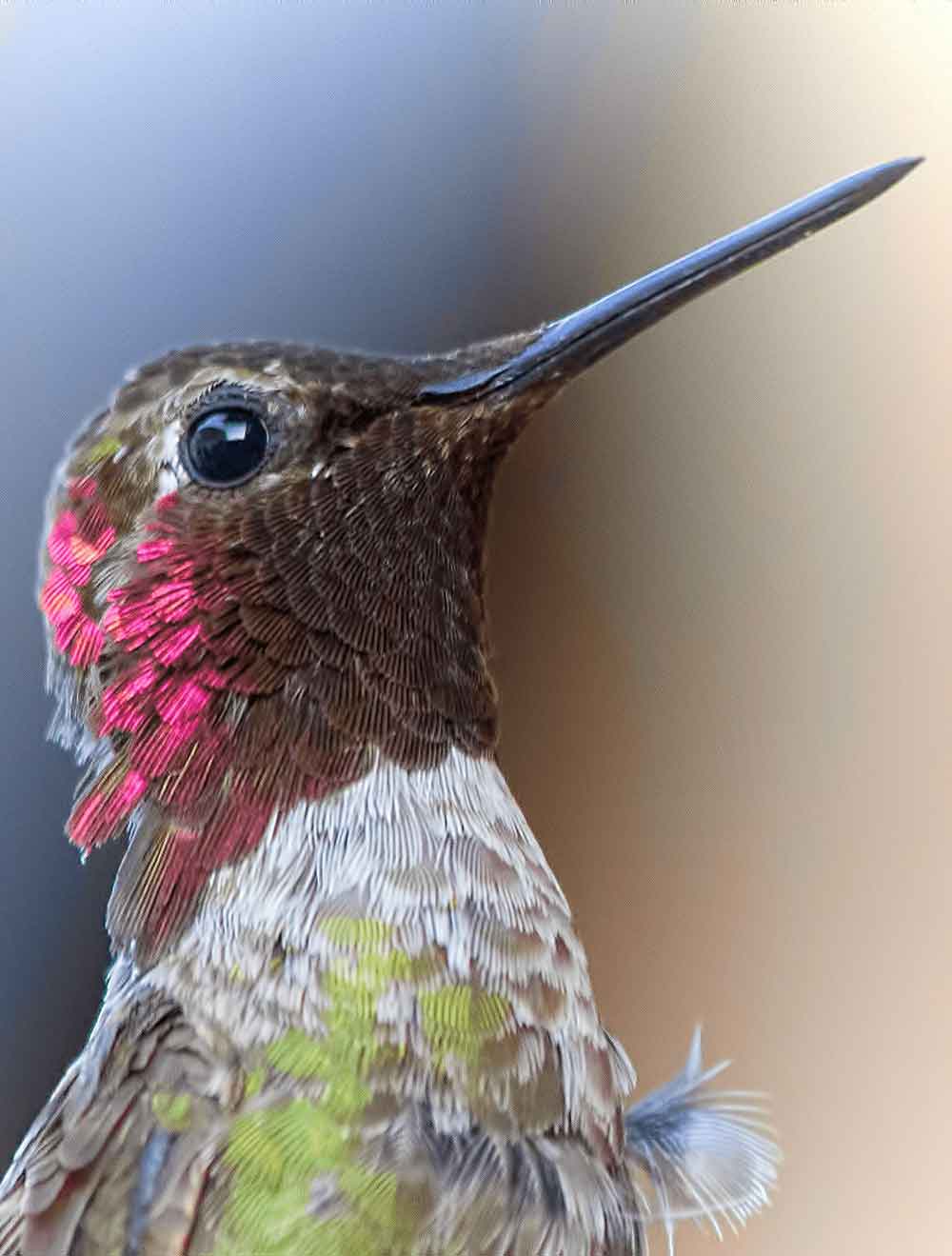

Perhaps one of the most colourful species common to the US is the Anna’s hummingbird, named after Anna de Belle Masséna the Duchess of Rivoli – a 19th-century noblewoman. Anna’s husband Prince François Victor Masséna was an amateur ornithologist who collected bird specimens. This hummingbird’s iridescent emerald and rose-pink plumage was described by naturalist René Primevère Lesson as “the bright sparkle of a red cap of the richest amethyst.”16

However, the greatest diversity of hummingbird species is found in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The smallest, the bee hummingbird of Cuba, weighs as little as 1.6g, little more than a standard paperclip. The biggest, meanwhile, is the northern giant hummingbird, which is native to the Andean highlands in South America. It measures around 23cm long and weighs in at roughly 20g, more than 10 times as much as the bee hummingbird. The sword-billed hummingbird, found in countries including Bolivia and Venezuela is notable because its beak is longer than its body.

Hummingbirds are found in North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. Only 15 species out of 366 breed regularly in the United States, the vast majority living further south.17 In fact, almost half of hummingbird species live within 10 degrees of latitude of the equator.18 The country with the largest number of documented hummingbird species is Columbia with 165 species, followed by Ecuador (132), Peru (124) and Venezuela (100).19

The islands of the Caribbean Sea are also home to many species of hummingbirds. They can be found on Jamaica, Cuba, Tobago, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, Aruba, Barbados and others. Trinidad alone has 19 species.

Although today hummingbirds are only found in the Americas, that was not always the case. The oldest hummingbird fossil, dated to around 30 million years ago, was discovered in Germany in 2004.20 Why they disappeared from Europe remains a mystery.

The smallest hummingbird is the bee hummingbird, which also happens to be the smallest bird of any kind. Found only in Cuba, bee hummingbirds measure just over 5cm long and weigh less than 2g, smaller than many insects.21 The largest hummingbird, on the other hand, is the Northern giant hummingbird, which is 23cm long and weighs roughly 20g, ten times more than the bee hummingbird.

If you think hummingbirds are small, imagine how miniature their nests are. Hummingbirds build nests out of lichen, moss and spider silk. The nests are hard to spot as they are hidden away in the forks of branches, along twigs, or buried deep inside bushes. The nest of the bee hummingbird, for instance, measures just 2.5cm across, while the eggs are about the size of a coffee bean.22 The nests of other small species are about the size of half a walnut shell.

Hummingbirds are the only birds that can hover in still air for 30 seconds or more, but this hovering requires a huge amount of energy – more than almost any other activity in the animal kingdom.23 To meet this energy demand, hummingbirds must consume a huge amount of food – around half their own bodyweight every day. Their diet consists of nectar, sap, insects, spiders, and the eggs of these creatures.

They are the world's hungriest birds, burning through energy at an incredible rate. In fact, hummingbirds have the fastest metabolic rate of any vertebrate on the planet. To put it in perspective, a human with the same metabolic rate would need to eat 300 pounds in weight of hamburgers a day.24

In fact, hummingbirds need to eat so much food that they'd starve overnight if they slept in a normal way. To conserve energy, hummingbirds enter a hibernation-like state called torpor at night, dropping their body temperature to under 4°C, and slowing their heartbeat.25

Hummingbirds are capable of incredible aerial acrobatics. They can fly forwards, hover on the spot, and can even fly backwards. This remarkable feat is down to their extremely flexible shoulder joints, which allow their wings to rotate 180 degrees.26One study found that flying backwards takes no more energy than flying forwards, and both are more energy efficient than hovering in mid-air.27Hummingbirds typically fly forwards to approach a flower, hover almost motionless during feeding, and then fly backwards when retreating. Backwards flight, therefore, is carried out by hummingbirds many dozens of times each day. Hummingbirds also occasionally fly backwards when interacting with other hummingbirds in mid-air.

Some species of hummingbirds can fly at speeds of over 33mph.28 In fact the male of one species, the Anna's hummingbird, can fly at a speed that puts even fighter jets to shame.29

To attract the attention of females, male Anna’s hummingbirds conduct death-defying dives, tucking in their wings and falling from the sky, before pulling up at the last second by spreading their tail feathers. In one study, Christopher Clark from the University of California in Berkeley filmed Anna’s hummingbirds conducting this stunt using a series of video cameras stationed around California’s East Shore State Park.30 To encourage the amorous birds to dive, he baited the males by presenting them with stuffed females and live caged birds, and then filmed their attempts in wooing.

The study revealed that during the dive, the tiny 7cm bird reaches a top speed of 60mph, flapping his wings 55 times per second, before tucking the wings in. At the fastest point of the dive, the male hummingbird covers 385 times his own body length every second. This is the fastest aerial manoeuvre performed by any bird relative to its size. For example, the peregrine falcon, while much faster in terms of miles per hour achieved, only covers 200 body lengths per second. A fighter jet at full throttle travels 150 body lengths per second, while a space shuttle re-entering Earth’s atmosphere travels at 207 body lengths per second.

According to Clark, pulling up at the last second subjects the hummingbird to g-forces that are nearly 10 times greater than the force of gravity (known as 10g). Fighter jet pilots are known to suffer blackouts and temporary blindness at accelerations of over 7g, as the blood drains away from the brain. However, the hummingbird suffers no such problem, as the pull-up manoeuvre lasts only a fraction of a second. Even so, the g-force puts a tremendous amount of pressure on the bird’s wings and shoulder joints, requiring the male to push back with his chest muscles to prevent his wings ripping apart.

Hummingbird tongues are a true evolutionary marvel. In 2011, scientists from the University of Connecticut used a high-speed camera and artificial see-through flowers to capture exactly what happens when hummingbirds drink nectar.31 They found that the birds use the tip of their tongue as a kind of dynamic liquid-trapping device. When it feeds, the hummingbird dips its long tongue into the flower and flicks it in and out 15 to 20 times per second.

The hummingbird has a forked tongue lined with hair-like extensions called lamellae. Whenever the tongue is dipped into the flower, the two forks separate, and the lamellae extend outwards. As the bird pulls its tongue in, the two tips come together and the lamellae roll inward, forming a kind of tube on each side of the tongue. Nectar is trapped within the tube. At the end of each lick, the hummingbird draws its tongue back into its bill, and the bill squeezes the tongue from above and below, squeezing out the nectar from the two tubes. When the bird sticks its tongue into the flower again, the tubes expand, which creates a vacuum which sucks nectar inside, similar to the action of a squeezy pipette.

The hummingbird’s tongue is remarkable in other ways too. In order to reach inside a flower and sip its delicious nectar, the hummingbird tongue needs to be very long. It is, in fact, so long that it requires extra support to hold it in place. When retracted, the hummingbird tongue wraps and coils around inside the bird's skull, reaching even behind its eye sockets.32

Shimmering purples, iridescent greens, sapphire blues, and splashes of dark violet – hummingbirds come in a dazzling array of colours. In fact, according to a 2022 study, hummingbirds are more colourful than all other bird species put together.33 The plumage of these fascinating birds even incorporates ultraviolet colours invisible to the human eye. The dazzling spectrum of colour is not created by pigments, but rather by the precisely arranged nanostructure of the hummingbird’s feathers.34 If you place a feather under the microscope and zoom in far enough you will see layers of tiny structures known as melanosomes. These contain melanin, a brown pigment. In between the melanosomes are tiny air pockets which scatter light. When light hits the feather, the melanosomes absorb a specific range of frequencies and reflect the rest of the light. That light is then scattered by the air pockets, creating an iridescent effect where intense bursts of colour appear only when light hits the feather at certain angles.

It's thought that hummingbirds use their bright colourful plumage to communicate with one another, attract mates, and mark their territories. For instance, as the iridescent flashes of light are dependent on the angle at which the sun hits the feathers, hummingbirds may use their aerial movements to produce bright flashes of colour to attract mates.35

Scientists have known for some time that birds have better colour vision that humans. Humans, like most primates, have three types of colour-sensitive receptors in their retinas: blue, green, and red. Together these receptors, known as cones, allow humans to detect the full spectrum of colours in the rainbow: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. However, birds have four cones: red, green, blue, and ultraviolet, suggesting they can see colours beyond the spectrum that we can’t even imagine. These include ultraviolet, and ultraviolet mixed with other hues like ultraviolet-yellow, ultraviolet-red, ultraviolet-purple and ultraviolet-green.36

In 2020, Mary Stoddard, a Princeton University evolutionary biologist, and colleagues trained wild broad-tailed hummingbirds near the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Colorado to associate a particular colour with the presence of a reward.37 The team set up two bird feeders, each with an LED device that could display a broad range of colours. One feeder contained sugar water (a tasty treat), while the other contained plain water. The hummingbirds quickly learned to associate the treat-filled feeder with a specific colour. Over three field seasons from 2016 to 2018, the scientists collected data on 6,000 hummingbird visits. The results showed that hummingbirds could correctly identify the feeder containing sugar water even when the colours emitted by the two LEDs looked the same to the human eye. The study provides evidence that hummingbirds can see a variety of colours outside of the rainbow spectrum, including purple, ultraviolet-green, ultraviolet-red and ultraviolet-yellow. Hummingbirds can easily distinguish ultraviolet-green from pure ultraviolet or pure green. It’s likely they use their remarkable colour vision to help them locate a diverse variety of plants and their nectar.

Hummingbirds are very intelligent birds. Hummingbirds visit hundreds of flowers every day, so to maximise their calorie intake they must remember the location of every flower they have visited, and the locations of the flowers with the richest nectar. Research shows they can do just that. For instance, one study showed they could remember the spatial location and distribution of flowers.38 Another showed they could recall the nectar volume and concentration of individual flowers.39 Meanwhile a third study showed hummingbirds were able to remember how long an individual flower on their territory takes to refill with nectar after they have fed.40

Scientists from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland found evidence that hummingbirds can keep track of where flowers are located by counting.41 The researchers placed 10 identical feeders in the territory of nine wild hummingbirds. One of the feeders contained sugar water while the rest were empty.

Once the birds figured out which feeder held the sugar water, the researchers moved the feeders to a new location but kept the order of the feeders the same. The birds were able to remember the order of feeders and correctly went to the right feeder to collect their sugary treat.

To help with this feat of memory, hummingbirds have the largest brain-to-body ratio of any bird, with their brain making up about 4.2% of their body weight.42 One study found that a hummingbird’s hippocampus – the area of the brain responsible for learning and memory – is up to five times larger than that of songbirds, seabirds and woodpeckers.43

Featured image © Denek Machacek | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Bill Williams | Unsplash

Quick facts:

1. Hannemann, Emily. “How Long Do Hummingbirds Live?” Birds and Blooms, 18 Jan. 2024, www.birdsandblooms.com/birding/attracting-hummingbirds/how-long-do-hummingbirds-live. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

2. “Hummingbirds of the United States: A Photo List of All Species.” American Bird Conservancy, 26 Apr. 2021, abcbirds.org/blog21/types-of-hummingbirds/.

3. IUCN. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” IUCN Red List, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 2025, www.iucnredlist.org/.

Fact File:

1. Brendan Borrell. Unlocking the secrets behind the hummingbird’s frenzy. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/hummingbird-secrets-speed-worlds-smallest-bird

2. Willow Defebaugh. 2022. Gentle Now: How Hummingbirds Hover. Atmos Earth. https://atmos.earth/facts-about-hummingbirds-and-how-they-hover/

3. Suarez, R.K. 1992. Hummingbird flight: Sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates. Experientia 48, 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01920240

4. Nancy Eilertsen. 2000. Why Does A Hummingbird Hum? Illinois Periodicals Online. https://www.lib.niu.edu/2000/oi000811.html

5. Peter Dockrill. 2020. Hummingbirds Can See Colours We Can't Even Imagine, Experiment Reveals. Science Alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/hummingbirds-can-see-colours-we-can-t-even-imagine-experiment-reveals

6. Riley Woodford. 2010. Long-Distance Hummingbird Sheds Light on Migration. Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=478

7. Ed Yong. 2009. Anna’s hummingbird outflies falcons and fighter pilots. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/annas-hummingbird-outflies-falcons-and-fighter-pilots

8. Eberts, E., C. G. Guglielmo, and K. C. Welch. 2021. Reversal of the adipostat control of torpor during migration in hummingbirds. eLife;10:e70062 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70062

9. Jon Dunn. 2021. Super pecs and 1,200 heartbeats per minute: The hidden biology of hummingbird flight. BBC Science Focus. https://www.sciencefocus.com/nature/how-the-hummingbird-evolved-the-animal-kingdoms-most-remarkable-flying-abilities

10. The Cornell Lab. All About Birds. 2024. 9 Hummingbird Species To Look Out For This Summer. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/summertime-in-the-united-states-of-hummingbirds/

11. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Interesting Facts on Hummingbirds. https://hummingbirds.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/information/facts

12. The Cornell Lab. All About Birds. Rufous Hummingbird Range Map https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rufous_Hummingbird/maps-range

13. Audubon Society. Ruby Throated Hummingbird. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ruby-throated-hummingbird

14. Riley Woodford. 2010. Long-Distance Hummingbird Sheds Light on Migration. Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=478

15. Abi Cole. 2024. Scientists Discover World’s Largest Hummingbird Hiding in Plain Sight. Audubon Magazine. https://www.audubon.org/magazine/scientists-discover-worlds-largest-hummingbird-hiding-plain-sight

16. North Island Wildlife Recovery Centre. Anna's Hummingbirds. https://www.niwra.org/post/anna-s-hummingbirds

17. Kathryn Stonich. 2021. Hummingbirds of the United States: A Photo List of All Species. American Bird Conservancy.

18. Hummingbird Species. Hummingbird Central. https://www.hummingbirdcentral.com/hummingbird-species.htm

19. Hummingbird Population by Country. 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hummingbird-population-by-country

20. Gerald Mayr. 2004. Old World Fossil Record of Modern-Type Hummingbirds. Science. 304,861-864(2004).DOI:10.1126/science.1096856

21. Birdnote. 2018. Get to Know the Bee Hummingbird, the World’s Smallest Bird. https://www.audubon.org/news/get-know-bee-hummingbird-worlds-smallest-bird

22. Birdnote. 2018. Get to Know the Bee Hummingbird, the World’s Smallest Bird. https://www.audubon.org/news/get-know-bee-hummingbird-worlds-smallest-bird

23. Willow Defebaugh. 2022. Gentle Now: How Hummingbirds Hover. Atmos Earth. https://atmos.earth/facts-about-hummingbirds-and-how-they-hover/

24. Nancy Eilertsen. 2000. Why Does A Hummingbird Hum? Illinois Periodicals Online. https://www.lib.niu.edu/2000/oi000811.html

25. Eberts, E., C. G. Guglielmo, and K. C. Welch. 2021. Reversal of the adipostat control of torpor during migration in hummingbirds. eLife;10:e70062 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70062

26. Erica J. Sánchez Vázquez. 2020.Ten Fascinating Facts About Hummingbirds. American Bird Conservancy. https://abcbirds.org/blog20/ten-fascinating-facts-about-hummingbirds/

27. Nir Sapir and Robert Dudley. 2012. Backward flight in hummingbirds employs unique kinematic adjustments and entails low metabolic cost. Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (20): 3603–3611 doi.org/10.1242/jeb.073114

28. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Interesting Facts on Hummingbirds. https://hummingbirds.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/information/facts

29. Ed Yong. 2009. Anna’s hummingbird outflies falcons and fighter pilots. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/annas-hummingbird-outflies-falcons-and-fighter-pilots

30. Clark Christopher James. 2009. Courtship dives of Anna's hummingbird offer insights into flight performance limits. Proc. R. Soc. B.2763047–3052 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0508

31. Deborah Braconnier. 2011. How the hummingbird’s tongue really works. Phys Org. https://phys.org/news/2011-05-hummingbird-tongue-video.html

32. Hummingbirds. Journey North. https://journeynorth.org/tm/humm/tongue_fluid_trap.html

33. Venable, G.X., Gahm, K. & Prum, R.O. 2022. Hummingbird plumage color diversity exceeds the known gamut of all other birds. Commun Biol 5, 576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03518-2

34. GrrlScientist. 2022. Hummingbirds are the most spectacularly colourful birds of all. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/grrlscientist/2022/06/26/hummingbirds-are-the-most-spectacularly-colorful-birds-of-all/

35. Hogan, B.G., Stoddard, M.C. Synchronization of speed, sound and iridescent color in a hummingbird aerial courtship dive. Nat Commun 9, 5260 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07562-7

36. Liz Fuller-Wright. 2020. Wild hummingbirds see a broad range of colors humans can only imagine. Princeton University. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2020/06/15/wild-hummingbirds-see-broad-range-colors-humans-can-only-imagine

37. M.C. Stoddard, H.N. Eyster, B.G. Hogan, D.H. Morris, E.R. Soucy, D.W. Inouye. 2020. Wild hummingbirds discriminate nonspectral colors, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (26) 15112-15122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919377117

38. Hurley T. A. 1996. Spatial memory in rufous hummingbirds: memory for rewarded and non-rewarded sites. Anim. Behav. 51, 177–183 10.1006/anbe.1996.0015

39. Bateson M., Healy S. D., Hurly T. A. 2003. Context-dependent foraging decisions in rufous hummingbirds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 1271–1276 doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2365

40. Henderson J., Hurly T. A., Bateson M., Healy S. D. 2006. Timing in free-living rufous hummingbirds, Selasphorus rufus. Curr. Biol. 16, 512–515 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.054

41. Vámos Tas I. F., Tello-Ramos Maria C., Hurly T. Andrew and Healy Susan D. 2020. Numerical ordinality in a wild nectarivore. Proc. R. Soc. B.28720201269 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1269

42. Holly Hastings. 2024. The Marvelous Mechanics of Hummingbirds. Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation. https://www.aiwc.ca/blog/the-marvelous-mechanics-of-hummingbirds/

43. Ward BJ, Day LB, Wilkening SR, Wylie DR, Saucier DM, Iwaniuk AN. 2012. Hummingbirds have a greatly enlarged hippocampal formation. Biol Lett. 23;8(4):657-9. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1180.

With some measuring as small as a human thumb, these lightning-fast birds are named after the “humming” sound their wings make as they beat at over 3,000 times a minute. Hummingbirds can fly forwards and backwards, and even hover in mid-air like tiny helicopters. These miniscule birds have such high metabolisms that to survive they must consume a colossal volume of nectar, equivalent in human terms to around 300 pounds in weight of hamburgers a day.

Chick

Bouquet, charm, shimmer

Cats, hawks, praying mantises, spiders, snakes, dragonflies, lizards, frogs, squirrels

Around 10 years in the wild, dependent upon species1

The smallest, the bee hummingbird of Cuba, measures just over 5cm long and is smaller than many insects. The biggest, the giant hummingbird, is around 23cm long

The bee hummingbird weighs as little as 1.6g – little more than a standard paperclip. The giant hummingbird weighs roughly 20g, more than ten times as much as the bee hummingbird

North America, Central America, South America, Caribbean islands

Dependent on species. There are approximately 34 million ruby-throated hummingbirds in the wild and 19 million rufous hummingbirds. However there are less than 200 violet-crowned hummingbirds and white-eared hummingbirds left in the wild.2

As of 2024, 8 hummingbird species are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. 13 are endangered, 13 are vulnerable, 21 are near threatened, and 317 are classed as ‘least concern’3

Hummingbirds have the fastest metabolic rate of any vertebrate on the planet relative to their size.

Hummingbirds can fly forwards and backwards, and even hover in mid-air like tiny helicopters.

Hummingbirds are lightning-fast tiny birds with eye-catching, colourful feathers that make them dazzle like jewels in the sun. With some having bodies as small as your thumb, hummingbirds beat their wings an average of 3,000 times per minute in a figure of eight pattern that creates lift on both the up and down strokes.10 Some hummingbirds can fly at speeds of over 33 miles per hour.11

They can hover in mid-air, fly upside down and backwards, and turn on a hairpin, displaying incredible acrobatic prowess. They are also the world’s smallest migratory bird, with some species flying upwards of 4,000 miles to reach their breeding grounds.12

There are approximately 366 species of hummingbirds. The most well-known species in the US is the ruby-throated hummingbird, which spends its winter in Mexico and Central America, before embarking on a marathon journey across the Gulf of Mexico to breed in Northern America – although some are known to fly around the Gulf of Mexico instead.13Some animals complete the journey in one non-stop flight. Rufous hummingbirds also complete a long migratory journey. For example, one rufous hummingbird was tracked more than 3,500 miles travelling from Florida to Alaska.14 The longest recorded migration of any hummingbird—a 5,200-mile round trip between the Chilean coast and the Peruvian Andes – meanwhile, can be attributed to the southern giant hummingbird.15

Other notable species common to the US include the black-chinned hummingbird – found in mountain forests, deserts, urban parks and woodlands – and the broad-tailed hummingbird, one of the noisiest hummingbirds thanks to the loud metallic trill that males produce with their wings. Allen’s hummingbirds, Costa’s hummingbirds and buff-bellied hummingbirds are also commonly seen in North America.

Perhaps one of the most colourful species common to the US is the Anna’s hummingbird, named after Anna de Belle Masséna the Duchess of Rivoli – a 19th-century noblewoman. Anna’s husband Prince François Victor Masséna was an amateur ornithologist who collected bird specimens. This hummingbird’s iridescent emerald and rose-pink plumage was described by naturalist René Primevère Lesson as “the bright sparkle of a red cap of the richest amethyst.”16

However, the greatest diversity of hummingbird species is found in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The smallest, the bee hummingbird of Cuba, weighs as little as 1.6g, little more than a standard paperclip. The biggest, meanwhile, is the northern giant hummingbird, which is native to the Andean highlands in South America. It measures around 23cm long and weighs in at roughly 20g, more than 10 times as much as the bee hummingbird. The sword-billed hummingbird, found in countries including Bolivia and Venezuela is notable because its beak is longer than its body.

Hummingbirds are found in North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. Only 15 species out of 366 breed regularly in the United States, the vast majority living further south.17 In fact, almost half of hummingbird species live within 10 degrees of latitude of the equator.18 The country with the largest number of documented hummingbird species is Columbia with 165 species, followed by Ecuador (132), Peru (124) and Venezuela (100).19

The islands of the Caribbean Sea are also home to many species of hummingbirds. They can be found on Jamaica, Cuba, Tobago, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, Aruba, Barbados and others. Trinidad alone has 19 species.

Although today hummingbirds are only found in the Americas, that was not always the case. The oldest hummingbird fossil, dated to around 30 million years ago, was discovered in Germany in 2004.20 Why they disappeared from Europe remains a mystery.

The smallest hummingbird is the bee hummingbird, which also happens to be the smallest bird of any kind. Found only in Cuba, bee hummingbirds measure just over 5cm long and weigh less than 2g, smaller than many insects.21 The largest hummingbird, on the other hand, is the Northern giant hummingbird, which is 23cm long and weighs roughly 20g, ten times more than the bee hummingbird.

If you think hummingbirds are small, imagine how miniature their nests are. Hummingbirds build nests out of lichen, moss and spider silk. The nests are hard to spot as they are hidden away in the forks of branches, along twigs, or buried deep inside bushes. The nest of the bee hummingbird, for instance, measures just 2.5cm across, while the eggs are about the size of a coffee bean.22 The nests of other small species are about the size of half a walnut shell.

Hummingbirds are the only birds that can hover in still air for 30 seconds or more, but this hovering requires a huge amount of energy – more than almost any other activity in the animal kingdom.23 To meet this energy demand, hummingbirds must consume a huge amount of food – around half their own bodyweight every day. Their diet consists of nectar, sap, insects, spiders, and the eggs of these creatures.

They are the world's hungriest birds, burning through energy at an incredible rate. In fact, hummingbirds have the fastest metabolic rate of any vertebrate on the planet. To put it in perspective, a human with the same metabolic rate would need to eat 300 pounds in weight of hamburgers a day.24

In fact, hummingbirds need to eat so much food that they'd starve overnight if they slept in a normal way. To conserve energy, hummingbirds enter a hibernation-like state called torpor at night, dropping their body temperature to under 4°C, and slowing their heartbeat.25

Hummingbirds are capable of incredible aerial acrobatics. They can fly forwards, hover on the spot, and can even fly backwards. This remarkable feat is down to their extremely flexible shoulder joints, which allow their wings to rotate 180 degrees.26One study found that flying backwards takes no more energy than flying forwards, and both are more energy efficient than hovering in mid-air.27Hummingbirds typically fly forwards to approach a flower, hover almost motionless during feeding, and then fly backwards when retreating. Backwards flight, therefore, is carried out by hummingbirds many dozens of times each day. Hummingbirds also occasionally fly backwards when interacting with other hummingbirds in mid-air.

Some species of hummingbirds can fly at speeds of over 33mph.28 In fact the male of one species, the Anna's hummingbird, can fly at a speed that puts even fighter jets to shame.29

To attract the attention of females, male Anna’s hummingbirds conduct death-defying dives, tucking in their wings and falling from the sky, before pulling up at the last second by spreading their tail feathers. In one study, Christopher Clark from the University of California in Berkeley filmed Anna’s hummingbirds conducting this stunt using a series of video cameras stationed around California’s East Shore State Park.30 To encourage the amorous birds to dive, he baited the males by presenting them with stuffed females and live caged birds, and then filmed their attempts in wooing.

The study revealed that during the dive, the tiny 7cm bird reaches a top speed of 60mph, flapping his wings 55 times per second, before tucking the wings in. At the fastest point of the dive, the male hummingbird covers 385 times his own body length every second. This is the fastest aerial manoeuvre performed by any bird relative to its size. For example, the peregrine falcon, while much faster in terms of miles per hour achieved, only covers 200 body lengths per second. A fighter jet at full throttle travels 150 body lengths per second, while a space shuttle re-entering Earth’s atmosphere travels at 207 body lengths per second.

According to Clark, pulling up at the last second subjects the hummingbird to g-forces that are nearly 10 times greater than the force of gravity (known as 10g). Fighter jet pilots are known to suffer blackouts and temporary blindness at accelerations of over 7g, as the blood drains away from the brain. However, the hummingbird suffers no such problem, as the pull-up manoeuvre lasts only a fraction of a second. Even so, the g-force puts a tremendous amount of pressure on the bird’s wings and shoulder joints, requiring the male to push back with his chest muscles to prevent his wings ripping apart.

Hummingbird tongues are a true evolutionary marvel. In 2011, scientists from the University of Connecticut used a high-speed camera and artificial see-through flowers to capture exactly what happens when hummingbirds drink nectar.31 They found that the birds use the tip of their tongue as a kind of dynamic liquid-trapping device. When it feeds, the hummingbird dips its long tongue into the flower and flicks it in and out 15 to 20 times per second.

The hummingbird has a forked tongue lined with hair-like extensions called lamellae. Whenever the tongue is dipped into the flower, the two forks separate, and the lamellae extend outwards. As the bird pulls its tongue in, the two tips come together and the lamellae roll inward, forming a kind of tube on each side of the tongue. Nectar is trapped within the tube. At the end of each lick, the hummingbird draws its tongue back into its bill, and the bill squeezes the tongue from above and below, squeezing out the nectar from the two tubes. When the bird sticks its tongue into the flower again, the tubes expand, which creates a vacuum which sucks nectar inside, similar to the action of a squeezy pipette.

The hummingbird’s tongue is remarkable in other ways too. In order to reach inside a flower and sip its delicious nectar, the hummingbird tongue needs to be very long. It is, in fact, so long that it requires extra support to hold it in place. When retracted, the hummingbird tongue wraps and coils around inside the bird's skull, reaching even behind its eye sockets.32

Shimmering purples, iridescent greens, sapphire blues, and splashes of dark violet – hummingbirds come in a dazzling array of colours. In fact, according to a 2022 study, hummingbirds are more colourful than all other bird species put together.33 The plumage of these fascinating birds even incorporates ultraviolet colours invisible to the human eye. The dazzling spectrum of colour is not created by pigments, but rather by the precisely arranged nanostructure of the hummingbird’s feathers.34 If you place a feather under the microscope and zoom in far enough you will see layers of tiny structures known as melanosomes. These contain melanin, a brown pigment. In between the melanosomes are tiny air pockets which scatter light. When light hits the feather, the melanosomes absorb a specific range of frequencies and reflect the rest of the light. That light is then scattered by the air pockets, creating an iridescent effect where intense bursts of colour appear only when light hits the feather at certain angles.

It's thought that hummingbirds use their bright colourful plumage to communicate with one another, attract mates, and mark their territories. For instance, as the iridescent flashes of light are dependent on the angle at which the sun hits the feathers, hummingbirds may use their aerial movements to produce bright flashes of colour to attract mates.35

Scientists have known for some time that birds have better colour vision that humans. Humans, like most primates, have three types of colour-sensitive receptors in their retinas: blue, green, and red. Together these receptors, known as cones, allow humans to detect the full spectrum of colours in the rainbow: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. However, birds have four cones: red, green, blue, and ultraviolet, suggesting they can see colours beyond the spectrum that we can’t even imagine. These include ultraviolet, and ultraviolet mixed with other hues like ultraviolet-yellow, ultraviolet-red, ultraviolet-purple and ultraviolet-green.36

In 2020, Mary Stoddard, a Princeton University evolutionary biologist, and colleagues trained wild broad-tailed hummingbirds near the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Colorado to associate a particular colour with the presence of a reward.37 The team set up two bird feeders, each with an LED device that could display a broad range of colours. One feeder contained sugar water (a tasty treat), while the other contained plain water. The hummingbirds quickly learned to associate the treat-filled feeder with a specific colour. Over three field seasons from 2016 to 2018, the scientists collected data on 6,000 hummingbird visits. The results showed that hummingbirds could correctly identify the feeder containing sugar water even when the colours emitted by the two LEDs looked the same to the human eye. The study provides evidence that hummingbirds can see a variety of colours outside of the rainbow spectrum, including purple, ultraviolet-green, ultraviolet-red and ultraviolet-yellow. Hummingbirds can easily distinguish ultraviolet-green from pure ultraviolet or pure green. It’s likely they use their remarkable colour vision to help them locate a diverse variety of plants and their nectar.

Hummingbirds are very intelligent birds. Hummingbirds visit hundreds of flowers every day, so to maximise their calorie intake they must remember the location of every flower they have visited, and the locations of the flowers with the richest nectar. Research shows they can do just that. For instance, one study showed they could remember the spatial location and distribution of flowers.38 Another showed they could recall the nectar volume and concentration of individual flowers.39 Meanwhile a third study showed hummingbirds were able to remember how long an individual flower on their territory takes to refill with nectar after they have fed.40

Scientists from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland found evidence that hummingbirds can keep track of where flowers are located by counting.41 The researchers placed 10 identical feeders in the territory of nine wild hummingbirds. One of the feeders contained sugar water while the rest were empty.

Once the birds figured out which feeder held the sugar water, the researchers moved the feeders to a new location but kept the order of the feeders the same. The birds were able to remember the order of feeders and correctly went to the right feeder to collect their sugary treat.

To help with this feat of memory, hummingbirds have the largest brain-to-body ratio of any bird, with their brain making up about 4.2% of their body weight.42 One study found that a hummingbird’s hippocampus – the area of the brain responsible for learning and memory – is up to five times larger than that of songbirds, seabirds and woodpeckers.43

Featured image © Denek Machacek | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Bill Williams | Unsplash

Quick facts:

1. Hannemann, Emily. “How Long Do Hummingbirds Live?” Birds and Blooms, 18 Jan. 2024, www.birdsandblooms.com/birding/attracting-hummingbirds/how-long-do-hummingbirds-live. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

2. “Hummingbirds of the United States: A Photo List of All Species.” American Bird Conservancy, 26 Apr. 2021, abcbirds.org/blog21/types-of-hummingbirds/.

3. IUCN. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” IUCN Red List, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 2025, www.iucnredlist.org/.

Fact File:

1. Brendan Borrell. Unlocking the secrets behind the hummingbird’s frenzy. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/hummingbird-secrets-speed-worlds-smallest-bird

2. Willow Defebaugh. 2022. Gentle Now: How Hummingbirds Hover. Atmos Earth. https://atmos.earth/facts-about-hummingbirds-and-how-they-hover/

3. Suarez, R.K. 1992. Hummingbird flight: Sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates. Experientia 48, 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01920240

4. Nancy Eilertsen. 2000. Why Does A Hummingbird Hum? Illinois Periodicals Online. https://www.lib.niu.edu/2000/oi000811.html

5. Peter Dockrill. 2020. Hummingbirds Can See Colours We Can't Even Imagine, Experiment Reveals. Science Alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/hummingbirds-can-see-colours-we-can-t-even-imagine-experiment-reveals

6. Riley Woodford. 2010. Long-Distance Hummingbird Sheds Light on Migration. Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=478

7. Ed Yong. 2009. Anna’s hummingbird outflies falcons and fighter pilots. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/annas-hummingbird-outflies-falcons-and-fighter-pilots

8. Eberts, E., C. G. Guglielmo, and K. C. Welch. 2021. Reversal of the adipostat control of torpor during migration in hummingbirds. eLife;10:e70062 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70062

9. Jon Dunn. 2021. Super pecs and 1,200 heartbeats per minute: The hidden biology of hummingbird flight. BBC Science Focus. https://www.sciencefocus.com/nature/how-the-hummingbird-evolved-the-animal-kingdoms-most-remarkable-flying-abilities

10. The Cornell Lab. All About Birds. 2024. 9 Hummingbird Species To Look Out For This Summer. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/summertime-in-the-united-states-of-hummingbirds/

11. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Interesting Facts on Hummingbirds. https://hummingbirds.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/information/facts

12. The Cornell Lab. All About Birds. Rufous Hummingbird Range Map https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rufous_Hummingbird/maps-range

13. Audubon Society. Ruby Throated Hummingbird. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ruby-throated-hummingbird

14. Riley Woodford. 2010. Long-Distance Hummingbird Sheds Light on Migration. Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=478

15. Abi Cole. 2024. Scientists Discover World’s Largest Hummingbird Hiding in Plain Sight. Audubon Magazine. https://www.audubon.org/magazine/scientists-discover-worlds-largest-hummingbird-hiding-plain-sight

16. North Island Wildlife Recovery Centre. Anna's Hummingbirds. https://www.niwra.org/post/anna-s-hummingbirds

17. Kathryn Stonich. 2021. Hummingbirds of the United States: A Photo List of All Species. American Bird Conservancy.

18. Hummingbird Species. Hummingbird Central. https://www.hummingbirdcentral.com/hummingbird-species.htm

19. Hummingbird Population by Country. 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hummingbird-population-by-country

20. Gerald Mayr. 2004. Old World Fossil Record of Modern-Type Hummingbirds. Science. 304,861-864(2004).DOI:10.1126/science.1096856

21. Birdnote. 2018. Get to Know the Bee Hummingbird, the World’s Smallest Bird. https://www.audubon.org/news/get-know-bee-hummingbird-worlds-smallest-bird

22. Birdnote. 2018. Get to Know the Bee Hummingbird, the World’s Smallest Bird. https://www.audubon.org/news/get-know-bee-hummingbird-worlds-smallest-bird

23. Willow Defebaugh. 2022. Gentle Now: How Hummingbirds Hover. Atmos Earth. https://atmos.earth/facts-about-hummingbirds-and-how-they-hover/

24. Nancy Eilertsen. 2000. Why Does A Hummingbird Hum? Illinois Periodicals Online. https://www.lib.niu.edu/2000/oi000811.html

25. Eberts, E., C. G. Guglielmo, and K. C. Welch. 2021. Reversal of the adipostat control of torpor during migration in hummingbirds. eLife;10:e70062 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70062

26. Erica J. Sánchez Vázquez. 2020.Ten Fascinating Facts About Hummingbirds. American Bird Conservancy. https://abcbirds.org/blog20/ten-fascinating-facts-about-hummingbirds/

27. Nir Sapir and Robert Dudley. 2012. Backward flight in hummingbirds employs unique kinematic adjustments and entails low metabolic cost. Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (20): 3603–3611 doi.org/10.1242/jeb.073114

28. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Interesting Facts on Hummingbirds. https://hummingbirds.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/information/facts

29. Ed Yong. 2009. Anna’s hummingbird outflies falcons and fighter pilots. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/annas-hummingbird-outflies-falcons-and-fighter-pilots

30. Clark Christopher James. 2009. Courtship dives of Anna's hummingbird offer insights into flight performance limits. Proc. R. Soc. B.2763047–3052 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0508

31. Deborah Braconnier. 2011. How the hummingbird’s tongue really works. Phys Org. https://phys.org/news/2011-05-hummingbird-tongue-video.html

32. Hummingbirds. Journey North. https://journeynorth.org/tm/humm/tongue_fluid_trap.html

33. Venable, G.X., Gahm, K. & Prum, R.O. 2022. Hummingbird plumage color diversity exceeds the known gamut of all other birds. Commun Biol 5, 576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03518-2

34. GrrlScientist. 2022. Hummingbirds are the most spectacularly colourful birds of all. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/grrlscientist/2022/06/26/hummingbirds-are-the-most-spectacularly-colorful-birds-of-all/

35. Hogan, B.G., Stoddard, M.C. Synchronization of speed, sound and iridescent color in a hummingbird aerial courtship dive. Nat Commun 9, 5260 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07562-7

36. Liz Fuller-Wright. 2020. Wild hummingbirds see a broad range of colors humans can only imagine. Princeton University. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2020/06/15/wild-hummingbirds-see-broad-range-colors-humans-can-only-imagine

37. M.C. Stoddard, H.N. Eyster, B.G. Hogan, D.H. Morris, E.R. Soucy, D.W. Inouye. 2020. Wild hummingbirds discriminate nonspectral colors, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (26) 15112-15122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919377117

38. Hurley T. A. 1996. Spatial memory in rufous hummingbirds: memory for rewarded and non-rewarded sites. Anim. Behav. 51, 177–183 10.1006/anbe.1996.0015

39. Bateson M., Healy S. D., Hurly T. A. 2003. Context-dependent foraging decisions in rufous hummingbirds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 1271–1276 doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2365

40. Henderson J., Hurly T. A., Bateson M., Healy S. D. 2006. Timing in free-living rufous hummingbirds, Selasphorus rufus. Curr. Biol. 16, 512–515 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.054

41. Vámos Tas I. F., Tello-Ramos Maria C., Hurly T. Andrew and Healy Susan D. 2020. Numerical ordinality in a wild nectarivore. Proc. R. Soc. B.28720201269 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1269

42. Holly Hastings. 2024. The Marvelous Mechanics of Hummingbirds. Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation. https://www.aiwc.ca/blog/the-marvelous-mechanics-of-hummingbirds/

43. Ward BJ, Day LB, Wilkening SR, Wylie DR, Saucier DM, Iwaniuk AN. 2012. Hummingbirds have a greatly enlarged hippocampal formation. Biol Lett. 23;8(4):657-9. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1180.

Chick

Bouquet, charm, shimmer

Cats, hawks, praying mantises, spiders, snakes, dragonflies, lizards, frogs, squirrels

Around 10 years in the wild, dependent upon species1

The smallest, the bee hummingbird of Cuba, measures just over 5cm long and is smaller than many insects. The biggest, the giant hummingbird, is around 23cm long

The bee hummingbird weighs as little as 1.6g – little more than a standard paperclip. The giant hummingbird weighs roughly 20g, more than ten times as much as the bee hummingbird

North America, Central America, South America, Caribbean islands

Dependent on species. There are approximately 34 million ruby-throated hummingbirds in the wild and 19 million rufous hummingbirds. However there are less than 200 violet-crowned hummingbirds and white-eared hummingbirds left in the wild.2

As of 2024, 8 hummingbird species are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. 13 are endangered, 13 are vulnerable, 21 are near threatened, and 317 are classed as ‘least concern’3

Hummingbirds have the fastest metabolic rate of any vertebrate on the planet relative to their size.